“Lashon hara,” literally “evil speech,” is generally categorized as any form of speech (or other form of communication) that denigrates someone, or any speech that could cause a person any sort of harm.

While it is generally well-known that lashon hara is prohibited by the Torah, it is quite possibly one of the most wholly-ignored commandments.

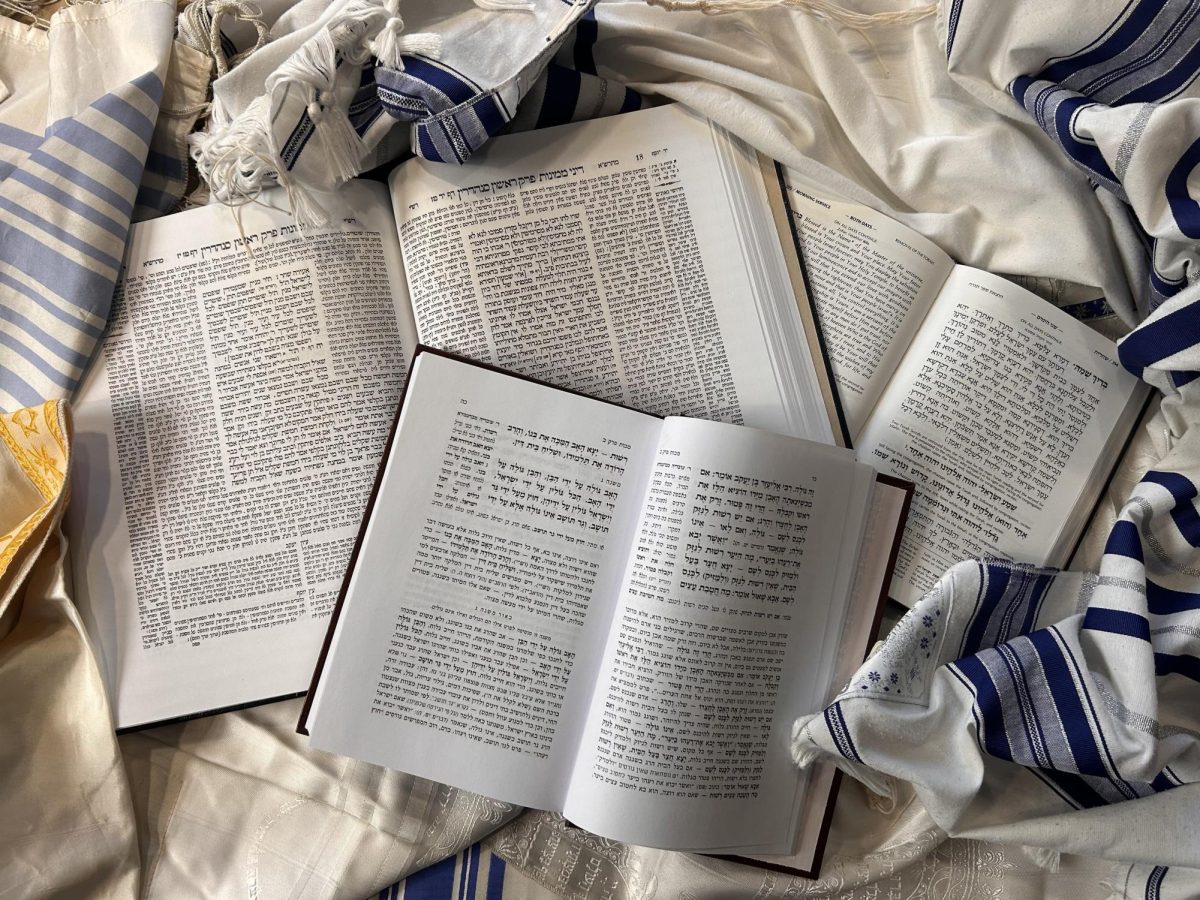

There are many prohibitive commandments in the Torah regarding lashon hara, but the most straightforward one is in Vayikra 19:16, “You shall not go around as a gossipmonger amidst your people.”

While it’s true that the idea of refraining from all gossip and unnecessary slanderous speech is a pretty idea that looks good on paper, it’s much easier said than done. And, in addition, what’s so bad about casually mentioning that so-and-so has bad taste in fashion? What harm could possibly come about through a comment like that?

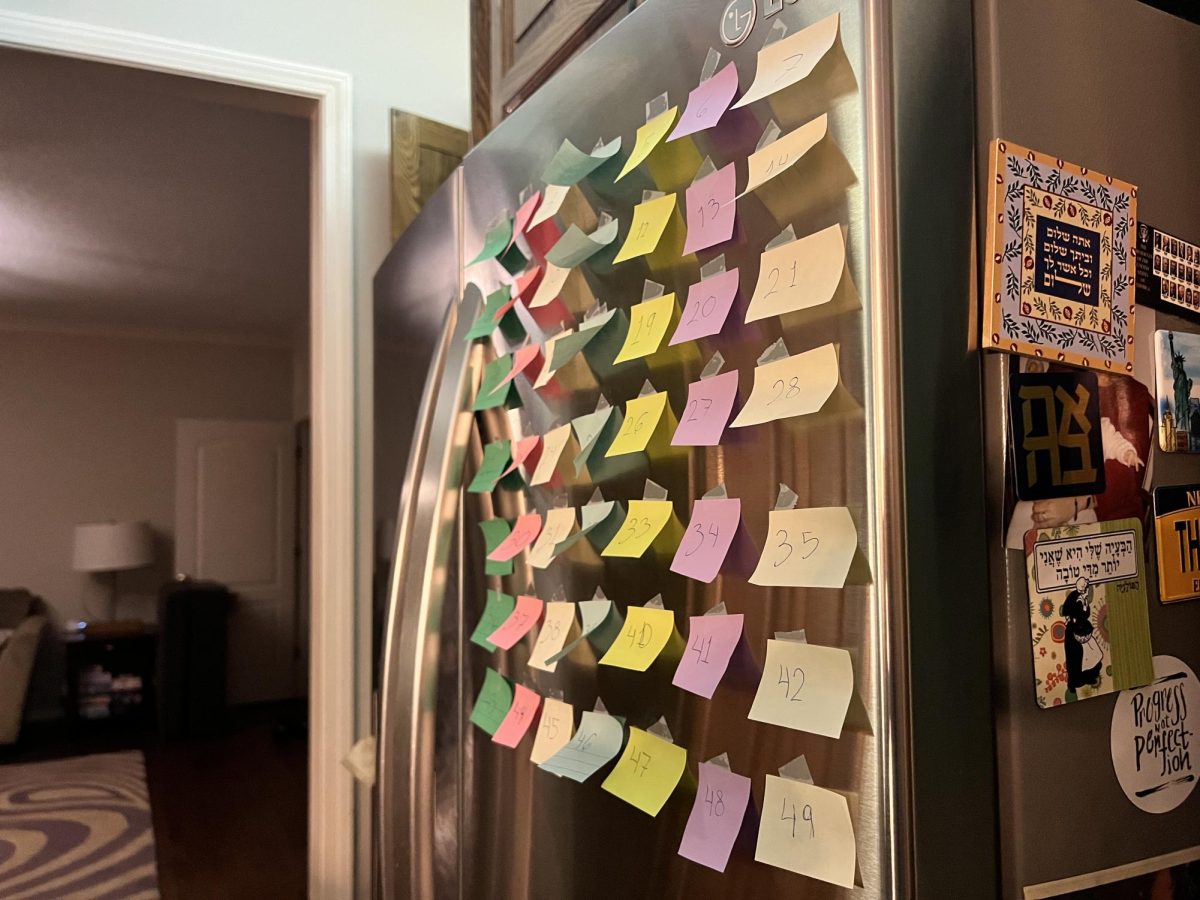

Rabbi Yehudah Zev Segal, a Manchester Rosh Yeshiva and student of the Chofetz Chaim, organized the Chofetz Chaim’s teachings into a daily study program. Based on this, Michael Rothschild authored a book entitled: “Chofetz Chaim: a Daily Companion.” All the information in this article will be taken from this book.

Let’s start by looking at why lashon hara is so frowned upon. The reasons for this can be divided up into four general categories: (1) The consequences of lashon hara. (2) The damage it does to others. (3) The damage it does to personal character, and (4) It’s despicable to Hashem.

We’ll begin with category (1), the consequences of lashon hara.

Rothschild explains that the reason the Second Temple was destroyed was due to sinat chinam (baseless hatred) and lashon hara. He further explains that “The 2,000-year-old exile is not a continuous punishment for the sins of those who lived during the Second Temple era.” If only people had stopped speaking lashon hara and hating each other needlessly, the Final Redemption would have come a long time ago.

Rothschild also cites and brings evidence to support lashon hara being the reason for the Egyptian exile and for the destruction of the First Temple.

Rothschild also explains something interesting about the “Heavenly judicial system.” He says that the judicial process in Heaven begins because of words which the Jews speak in this world. He then quotes Arachin 15b, “Whoever speaks loshon hora raises sins to the heavens.”

So clearly, engaging in lashon hara conversation might not be the ideal pastime. It caused both Temples to be destroyed, it’s the reason we haven’t yet been redeemed, and, as the book quotes from the Zohar, “[Through evil talk,] Satan is aroused to voice accusation against the entire world.” So definitely, less than ideal.

But this still doesn’t answer our deeper question, that question being, “Why is lashon hara so frowned upon?” We know the consequences, but not the reason those severe consequences exist.

Instead of focusing on the negatives of lashon hara, let’s instead look at the positives of not speaking lashon hara. Here we’ll begin category (2), the effect of lashon hara on other people.

Rothschild explains that lashon hara can be detrimental to a person’s mental health and self-image. Although you think that no one is going to repeat what you said and that your words won’t go anywhere, this is almost never true. Someone casually mentions it to someone, and that person casually mentions it to someone else, and eventually, it gets back to the subject of the derogatory comment.

As Rothschild says, “words can hurt – and they can hurt a lot; sometimes even more than physical abuse.”

It’s also noteworthy to mention that lashon hara can cause actual financial damage. For example, someone mentioning that a certain store is overpriced, or that the customer service is bad, could cause someone to pick a different store to buy from based on that comment alone, causing the owner of the store an unnecessary loss in business.

(It’s important to point out that there are certain situations in which “lashon hara” would be permitted, and even required. The Chofetz Chaim gives seven conditions which must be fulfilled in order to speak “lashon hara” for a constructive purpose. Other halachic authorities offer slightly different conditions.)

The same ideology that prohibits lashon hara promotes judging others in a favorable light. There are many benefits to this, one of them being that often when you judge someone and decide that what they’re doing is bad, you later learn that you were wrong in your judgment. But unfortunately, your words can’t be taken back.

Another benefit is that when trying to judge someone favorably, you put yourself in their shoes. This enables you to empathize with them, and consequently, instead of hating them and ranting about their misdeed, you instead develop a greater connection with them and become more compassionate.

Let’s get into categories (3) and (4). These categories are personal character damage and Hashem’s objections to lashon hara, respectively.

Another good reason to abstain from lashon hara is that it is simply the conduct of lowlives. As Rothschild puts it, “[A] Jew should have no interest in hearing his fellow man being degraded. Rather, he should live by the words of Rabbeinu Yonah: ‘The correct path is to conceal the sins [of others] and to praise a person for the good which can be found in him…’”

To put it simply: seeking and speaking of the wrongdoings and embarrassments of others is low. But to instead search for the good in someone and highlight it, that’s conduct worthy of admiration.

Finally, Rothschild writes, “[W]e see again and again that Hashem has great displeasure when His children are portrayed in a negative light… Hashem is telling us: ‘All of you are My children; please treat each other with respect and sensitivity.’”

Lashon hara destroys relationships, fosters animosity among friends, hurts feelings, taints character, destroyed both Temples, and is preventing the third one from being built.

With the absence of lashon hara, our love for each other is strengthened. We are more united and understanding of others, and embarrassment, animosity, and judgment are nearly eradicated.

The Temples were destroyed because of sinat chinam, baseless hatred. The only way to rebuild it is to practice ahavat chinam, that is, to love without, and beyond reason.