Slavery is a concept all-but-foreign to America. The horrors of American chattel slavery are well-known, and its atrocities cannot be forgotten. It’s denounced as a sin of pure evil, something utterly unacceptable in any form.

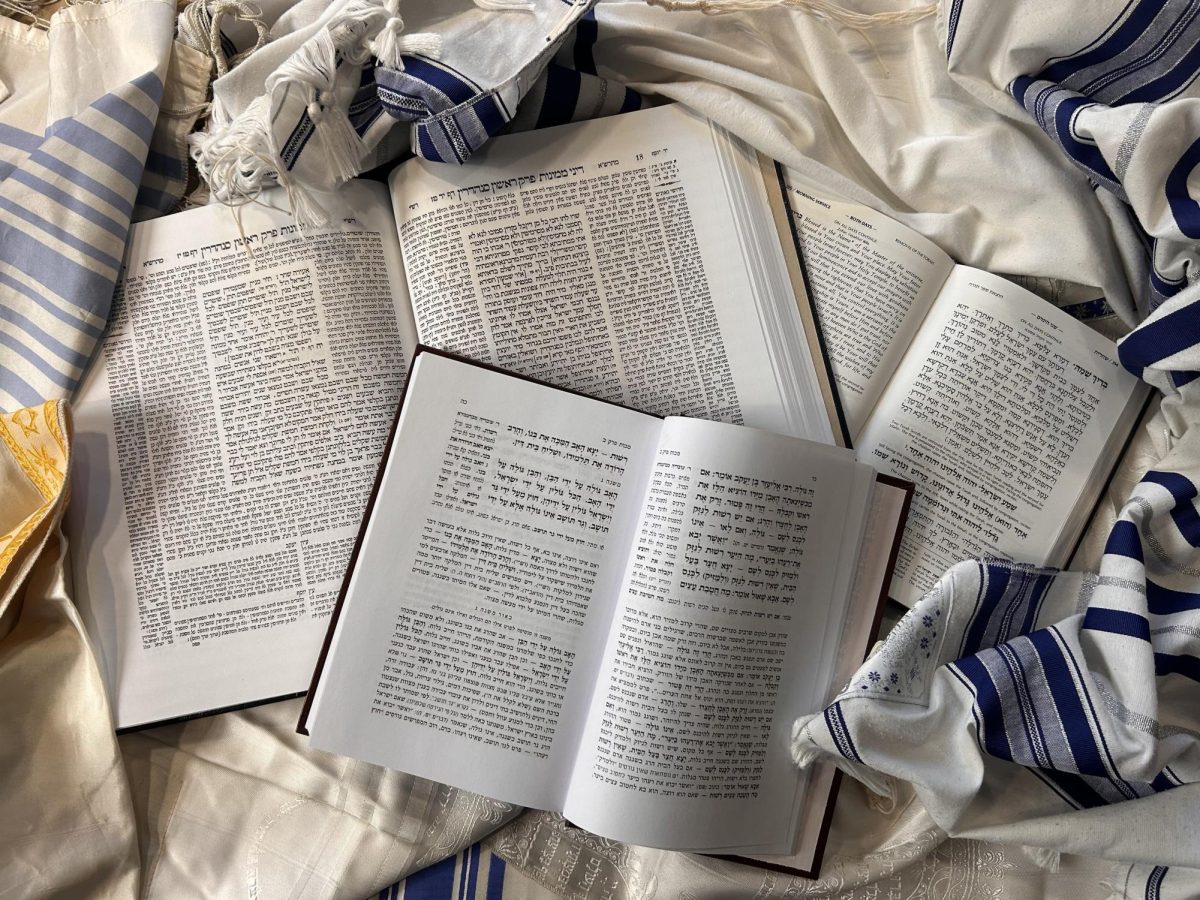

Yet, Parshat Mishpatim begins with the laws of slaves. How is it possible that the Ultimate Moral Compass, the Torah which supposedly contains all the world’s knowledge, permits slavery?

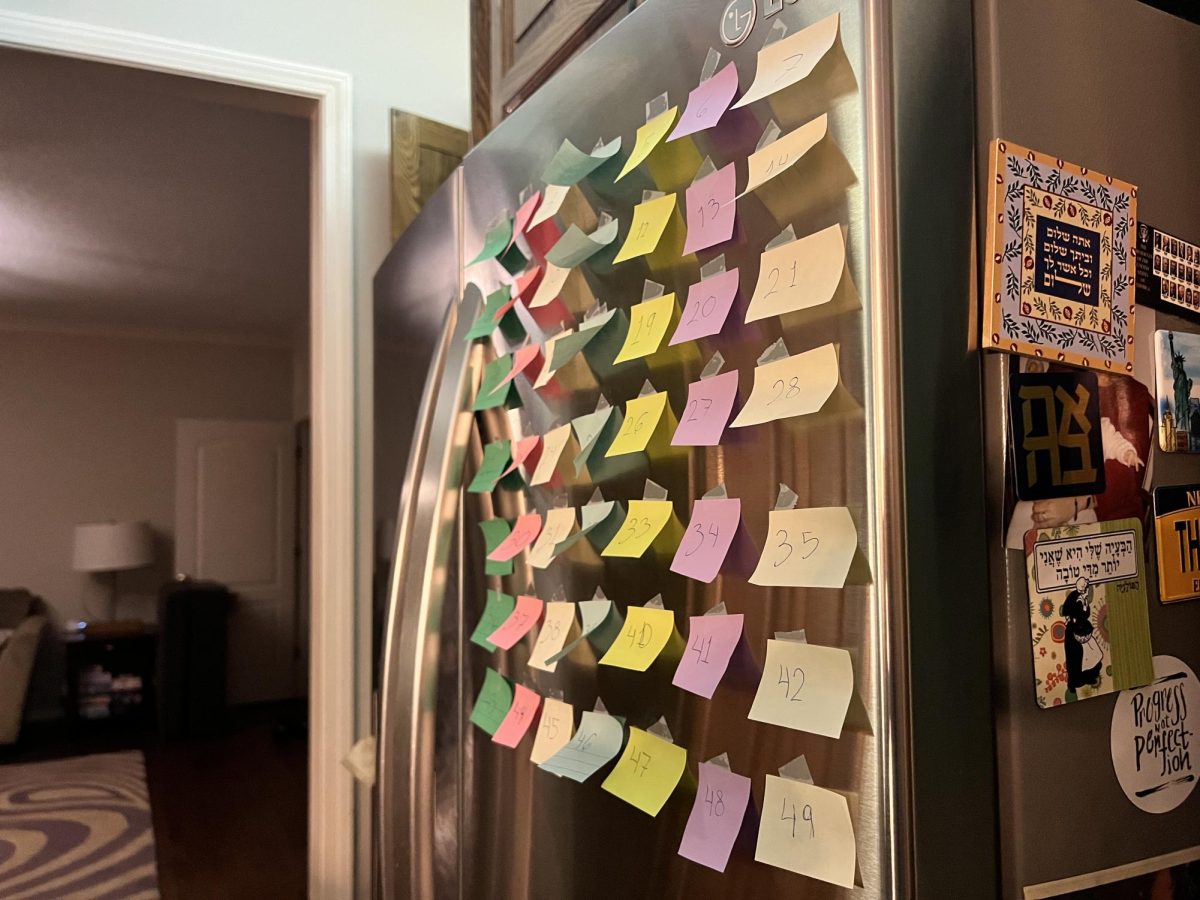

Let’s investigate, starting with the basic laws of slaves. The information below is taken from Rabbi Mendel Kaplan’s videos on Rambam’s Sefer HaMitzvot on Chabad.org.

In ancient Israel, Jewish slaves could be sold either by themselves, because they are destitute, or by the court. They could also be sold by the court for committing a theft which cannot be paid back. The thief would be sold to a master, who in turn would pay the slave’s wage to the court to compensate for the theft.

Women, even if they commit a theft, can never be sold as slaves, because it’s likely they’ll be sexually abused.

When the slaves are sold, they must be sold privately and not in a demeaning way (for example, they may not be sold at a typical slave market). Additionally, the Jewish court may only sell the slaves to Jews.

The slaves’ masters cannot make them do work that is demeaning for them. This includes a prohibition against telling a male slave to do “women’s work.” The slave also cannot be told to do work that is unnecessary just for the sake of looking productive.

An interesting law is that the slave must be treated the same way the master treats himself. This means that if the master lives in a nice house, the slave must also live in a nice house, and if the master only drinks aged wine, he must also only give his slave aged wine. There is even a law that if the master owns only one pillow, the one pillow must be given to his slave.

Non-Jewish slaves had slightly different laws. They don’t have all the protections that Jewish slaves had, but one thing is clear: They cannot be abused in any way. If they are abused, they go free immediately (and it goes without mention that sex slaves are prohibited).

That’s not too bad, right? No abuse, no embarrassment, and no sexual harassment. That’s all great, but that still doesn’t answer why the Torah allows slavery in the first place. Wouldn’t it be better if it just completely outlawed slavery instead of placing restrictions on it?

In short, not necessarily.

Rabbi Tzvi Freeman, in a Chabad.org article, writes: “The Torah must deal with the world as it is, not artificially imposing upon it a foreign mold, but bringing it on its own from the place it stands by nature and circumstance to the place it truly belongs.”

In simpler words, he means that telling a world engrossed in slavery (remember, these laws were originally given thousands of years ago) to completely abolish it wouldn’t have the most productive results. It’s too radical of a change.

But to instead allow slavery, while at the same time placing restrictions upon it, forcing the master to treat the slave in a humane way, that’s something that could lead to serious progress.

Rabbi Etan Ehrenfeld, in a lecture on Torah slavery, quotes Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, who said that being sold into slavery as a means of repaying a theft is a merciful punishment. Instead of being imprisoned or flogged, he is brought into a family, where he is cared for and treated as a member of their household. It’s a form of rehabilitation. He maintains his dignity, and his family is provided for financially.

Slavery, especially American slavery as we know it, is absolutely horrific. However, American chattel slavery, and the modern perception of slavery, is not the same as slavery outlined by the Torah and a distinction needs to be made.

The Torah is the ultimate guide to the world, and it’s important to remember that before we make judgements about its moral accuracy based on our own thinking. After all, I think it goes without saying that the Torah might know a little more than we do.

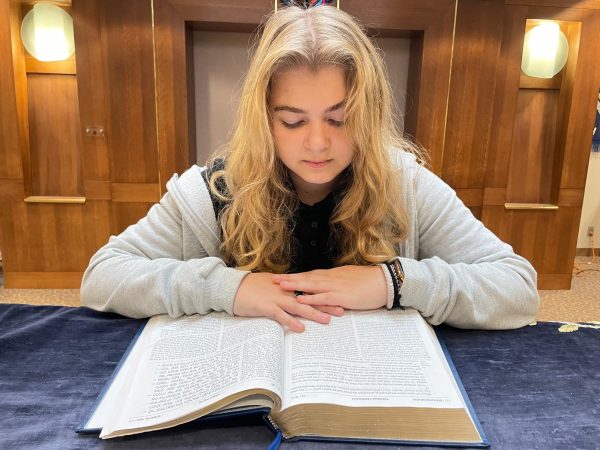

It’s true that there are some things in the Torah that make us uncomfortable, but this is a good thing. For discomfort encourages passionate investigation where we can, perhaps, learn even more about the Torah than if we found the morality in it immediately.