The obligation of self-affliction by fasting on Yom Kippur looks wildly different in the eyes of each individual. The effect fasting may have on one’s Jewish identity is all up for interpretation. To attempt to better understand the abstruse idea of the mitzvahs embodied in Yom Kippur, we must collect the opinions of those experiencing them first-hand.

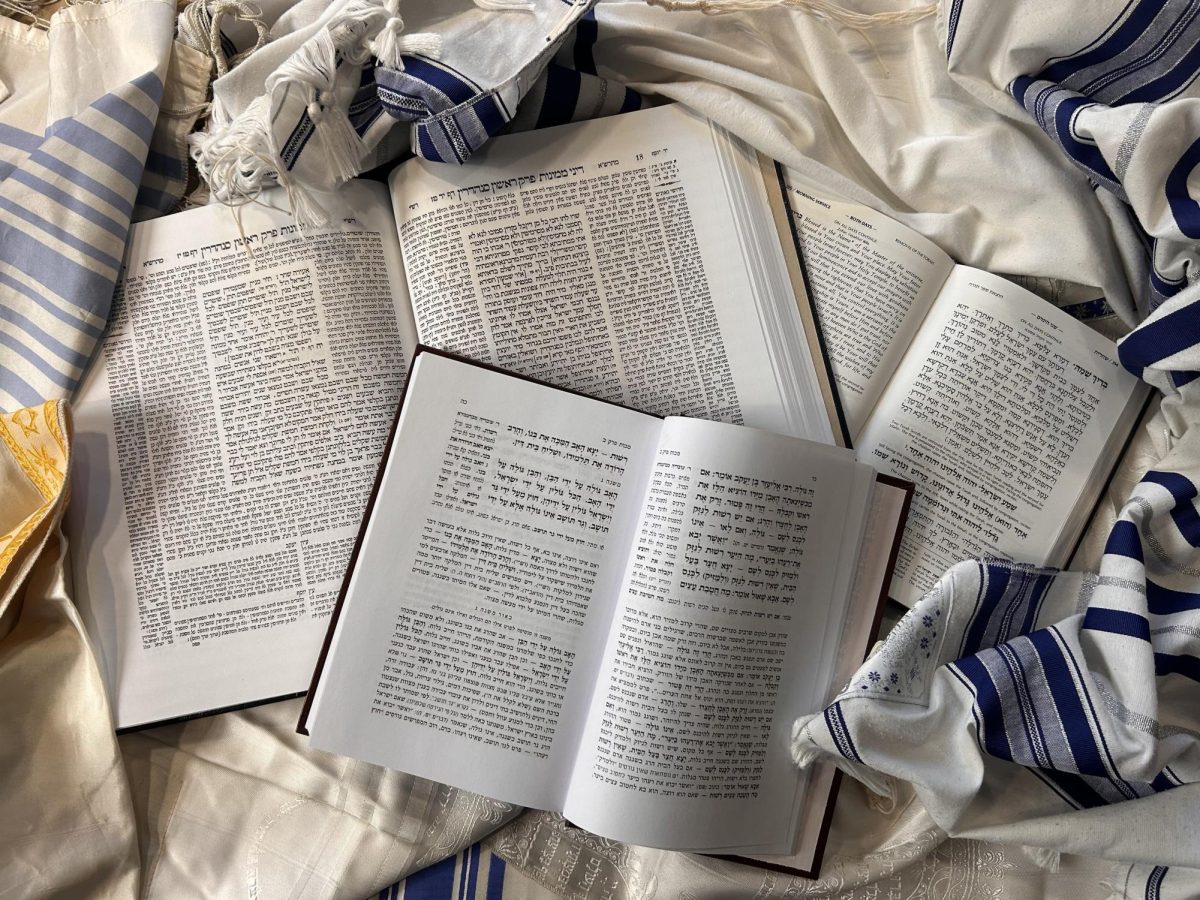

Jewish tradition, stemming from certain verses in the Torah, stipulates that fasting on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, is a necessary component of the day. The verse in the Torah, Leviticus 23:27, states that the Day of Atonement should be one of “self-denial”(roncantor.com). As Torah-observing and committed Jews, we have received a direct commandment to self-afflict on Yom Kippur, but the Torah does not directly allude to some of the other fast days, including the Fast of Esther. This may be why many overlook some of the other fasts and only choose to observe the fast of Yom Kippur.

There is a certain level of vulnerability that comes with self-affliction and how you choose to observe the mitzvah. Though as Jews we are told to “self-afflict” on Yom Kippur, we are never given a strict definition of how we are supposed to do so, resulting in the majority choosing to fast to fulfill the mitzvah of affliction.

Understanding the true definition of obligation as a whole is important before exploring the idea of fasting. Furthermore, each Jew must distinguish the level of importance the obligation of self-affliction is to them and how they choose to fulfill this commandment.

The direct meaning of obligation is “an act or course of action to which a person is morally or legally bound; a duty or commitment,” but when considering a religious standpoint, there is never one correct interpretation (Oxford Dictionary).

Uriel Noorollah, a freshman at HBHA said, “I think obligation means something you’re supposed to do if you’re able to, or something you can try your best to accomplish.” In contrast, HBHA senior Noa Levine explained how you can choose certain obligations to observe to which you feel most connected, and it doesn’t reflect negatively on you or your personality.

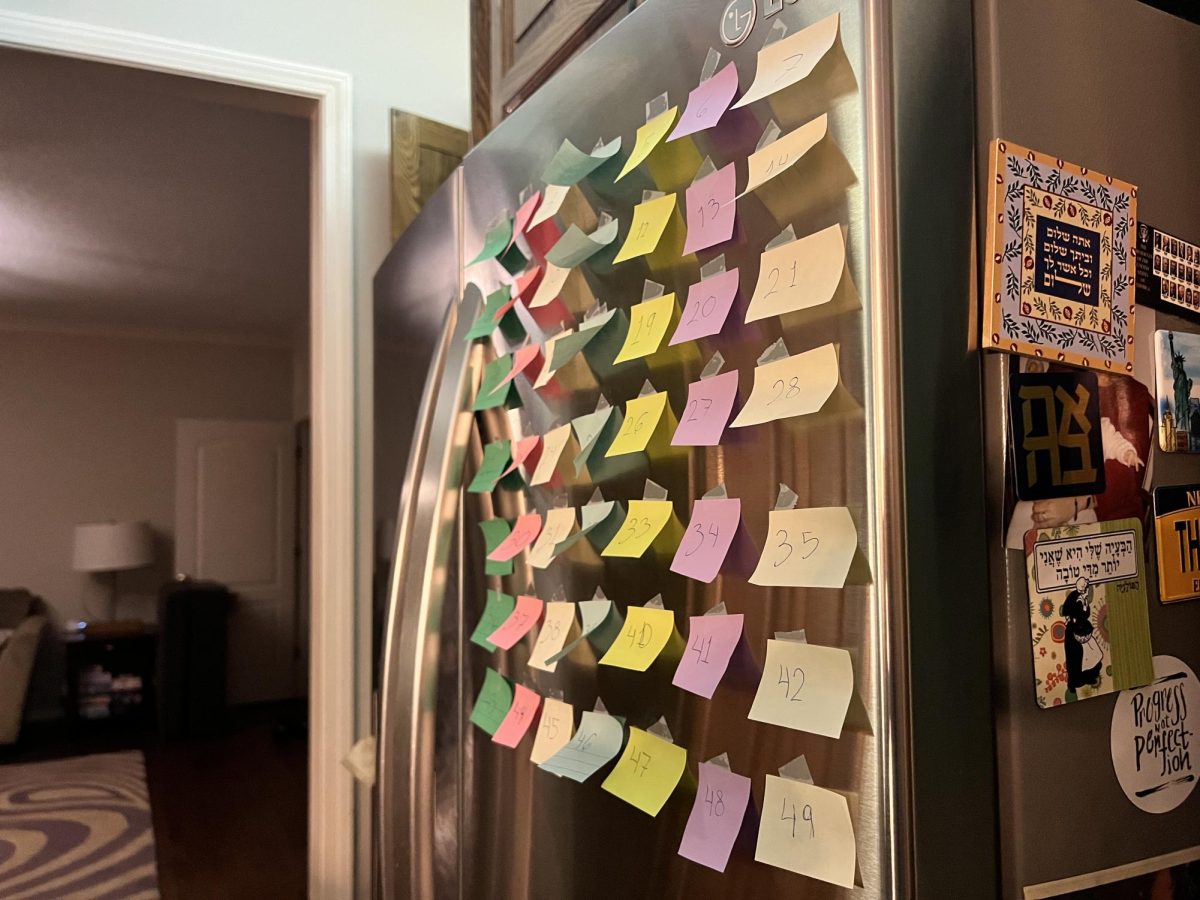

Picking and choosing whether we are self-afflicting on Yom Kippur may not be up for interpretation, but the way we choose to do so is meant to reflect each individual’s Jewish identity and the freedom we each have within the Jewish religion. Who is to say that fasting is the way we should be self-afflicting at all? Being in services for hours on end may be inflicting enough pain on ourselves as it is.

One of the many extraordinary things about Judaism is the ability to sculpt your own beliefs and interpretations. Self-affliction on Yom Kippur is one of our many chances to do this.

“I think of obligation as being a parallel concept to responsibility,” said Rita Cortes, a local Jewish Community member. She expressed how one of the beautiful distinctions of Judaism is not what it gives to us, but the responsibilities that we take on to both ourselves in our relationship with God and in our relationship with the community.

The biblical purpose of fasting is to take your mind off of food and allow you to focus on affliction and repentance regarding your sins. “[Fasting] seems like a very effective way of afflicting yourself without actually harming yourself,” Noorollah adds.

Self-affliction begins to get a little more ambiguous when considering whether one is fulfilling the true obligation of Yom Kippur if they don’t fast. Rhys Pabst, an eighth grader at HBHA responded with a straightforward answer that if you do not fast, you are not fulfilling the obligation or mitzvah. However, Levine added that a little food or water can be “beneficial” to refocus you on your repentance.

This idea ties back to the true question at hand whether fasting is the only way one can self-afflict. Pain is such a relative and personal concept similar to each person’s connection to Judaism. There are many layers of difficulty that lie within all the mitzvot and how we each interpret and fulfill them.

“The fasts aren’t meant to be easy,” Cortes explained, “but they are meant to help elevate the meaning [of Yom Kippur].” She continued, saying that if drinking or eating a little allows you to maintain the meaning of the holiday, then it is not considered a failure of obligation as there may be other ways the individual chooses to self-afflict.

Cortes took on the leadership role of leading the entirety of Yom Kippur services at Congregation Beth Shalom. When reflecting on this responsibility to fast, she said, “I thought it was going to be much harder than it turned out to be.”

This form of leadership from anyone on a holiday so high in importance can help recenter and reflect on the true meaning of the day, further allowing one to connect with their Jewish identity.

Fasting leaves many in a state of exhaustion which can often result in a less meaningful experience, especially if you are trying to focus on singing and praying all day long; but when considering the true reasons we are observing this mitzvah, “the idea of fasting for a full day just to solely focus on prayer is pretty powerful … you are asking G-d for another year of life,” Noorollah said.

Self-affliction is the type of experience where what you get out of it reflects what you put into it.

It is crucial never to put yourself in harm’s way when observing any mitzvah. We are taught as Jews that if there is any uncertainty in the well-being of an individual while they are fasting, it is always better to refrain.

The obligation of self-affliction and the stress that it puts on one’s Jewish identity looks different in the eyes of every Jewish individual. All you can do is try your best and fulfill your own beliefs above all else. That is the true meaning of Judaism.