Tzniut [Tznee-Oot], translated as Modesty, refers to the Torah laws of etiquette and behavioral conduct, expounded on by rabbis, which shape how people interact with others in the community. In Judaism, tzniut tends to be a trigger word for restricting women’s dress so that men don’t get distracted (from their Torah study) or get tempted to have illicit relations.

There is a perception that even when someone chooses to live in a community with a strictly modest dress expectation, the mob mentality of “Shtarkness” “The Yiddish for religiosity” makes for a suffocating culture of conformity and lack of personal expression. In the opposite direction, if someone doesn’t wear a skirt or cover their shoulders, they are seen as loose and seeking attention for their bodies. Why is tzniut looked at in a negative way?

This is largely due to the fact that in Jewish day schools, tzniut is only emphasized as a dress code and is inherently more enforced for girls, without explaining its purpose. This is evident at religious Jewish schools across America. Rather than doing away with dress codes altogether, schools should try to address the attitude towards them. Students should be encouraged to learn the positive qualities that it can have, and schools should listen to students when they feel that there is a disparity in the way it’s being enforced between boys and girls. A proper way of dress is certainly on the surface of tzniut, but the concept is much deeper and nuanced than what is realized.

At The Frisch School, one of the biggest modern-orthodox Jewish high schools, located in Paramus, N.J., girls are required to wear a skirt down to the knee and have their shoulders covered, and boys must wear a kippah and tzitzit as well as wearing a collared shirt. This minimal dress code is favored by students as it allows for personal fashion expression. The issue is that in coed schools, tzniut comes across as a mitzvah that only applies to women.

“You started getting skirted in middle school,” said a female student at Frisch, who went to Yavneh Academy, also in Paramus, N.J., for lower and middle school. She described the dress code as more relaxed in lower school, but starting in middle school, if a girl’s skirt isn’t to the knee, the student is either pulled aside and told to tug their skirt down or sent an email from an anonymous teacher at the end of the day, telling them not to wear that skirt again. This is a very frequent occurrence for girls in the student body, but when boys don’t wear the proper dress code they are rarely reprimanded.

“With women it’s easier to get caught up in the nitty gritty details,” says a Frisch alumni, Amalya Knapp, “with men too they should emphasize that you should wear a collar, you should wear tzitzit (fringes).” If the mitzvah of tzniut is both applicable to men and women, it should be encouraged to boys and girls equally in schools. This would prevent girls from feeling overly scrutinized, simply because they are girls, and it would take attention away from the sexual differences that tend to make girls the focus of tzniut.

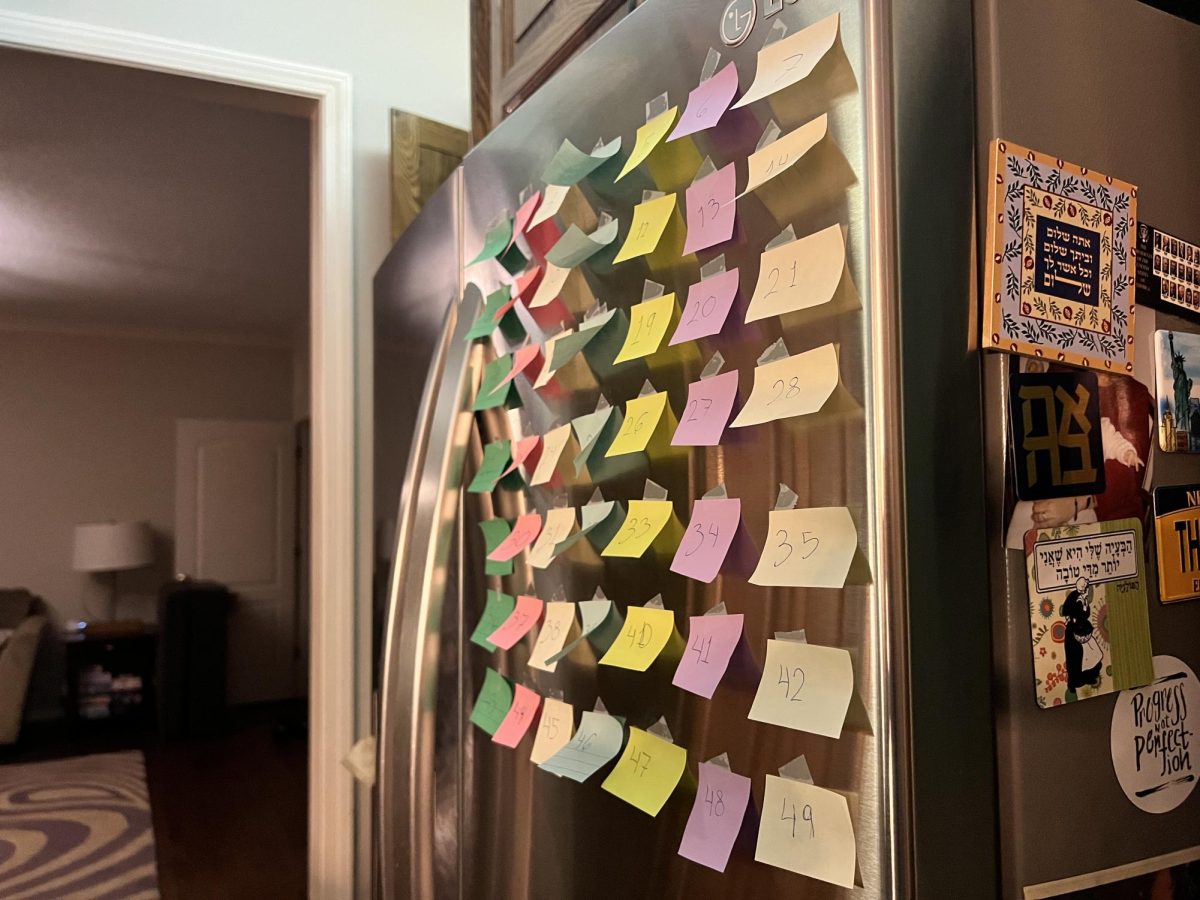

By the time you get to high school in many modern orthodox schools “they expect you to know it (tzniut),” recalls the female student at Frisch. She elaborates, “wear a skirt, cover your knees, cover your collarbone.” The automated “skirts need to touch the knee” is something girls have been hearing since middle school, and the focus on precise measurement has numbed students to the purpose of the dress code. Yet, students’ attitudes towards dress code isn’t going to change unless there is a connection to the underlying message of it.

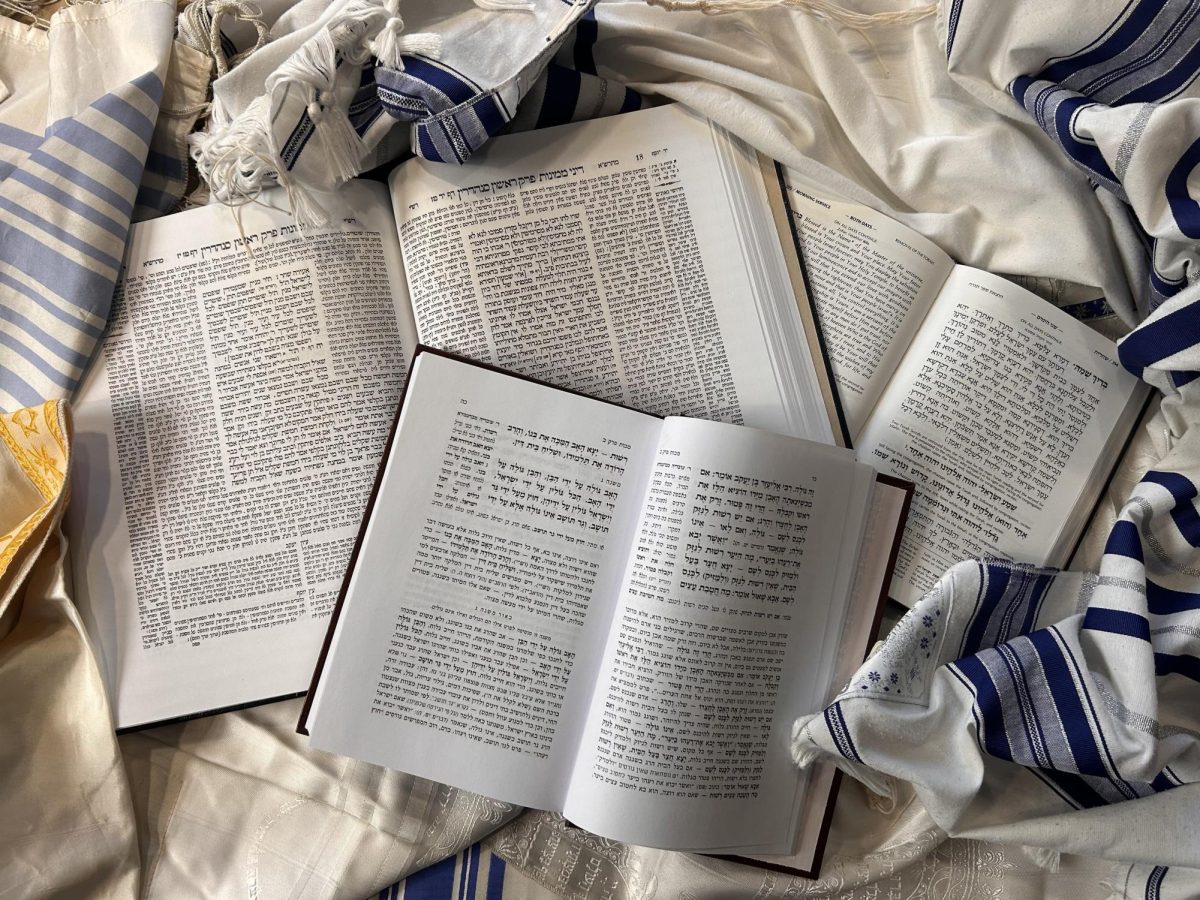

As a traditional Jewish principle, tzniut is not something meant to be oppressive to women, and the way to solve the dress code problem in schools is not to get rid of it, but rather to interact with it. The thing many schools are lacking is the “why,” so to fix this schools should turn to texts from the Torah and Talmud to explain it. Having many capable teachers to teach tzniut from Chazal (250 BCE – 625 CE) texts, but not offering these subjects, is a missed opportunity.

Diving into the Mishnah to explain modesty to second graders probably wouldn’t be effective. Knapp, Frisch Alumni, says what should be done regarding younger students is “emphasizing tzniut as more of a way to act than a way to dress.” Establishing a healthy relationship and understanding of tzniut is extremely important in primary education years as building blocks to grow on when the time is appropriate.

“A big part of it is how we dress, but it’s absolutely not what tzniut is all about,” says Chani Sosover, a lower school Judaics teacher at HBHA. Sosover is a Hasidic Jewish woman and grew up religious, attending an all-girls school. Getting at the essence of tzniut, Sosover says, “It’s about making space for someone else.”

The concept of contracting oneself to make room for creation is called TzimTzum, and it is said that Hashem did this when starting creation. One of the reasons why humans were made is so we could develop relationships with Hashem and other people. If we want to connect with others, we have to metaphorically take a step back to give room for the other person. This means not flaunting money, smarts, or the body.

Tzniut also has a lot to do with context. For example, it would be inappropriate to show up to a fancy wedding in jeans, and it would be inappropriate to go to the gym in a gown. “When I’m talking to somebody, it’s not about my body, it’s about my essence. It’s about who I am,” Sosover says. In general, tzniut is about not drawing inappropriate attention to oneself so that relationships can be formed in a deeper way and for dignified reasons.

Even with an understanding of why there are tzniut laws, many people struggle with why these are different for men and women. Sosover puts it like this; “Hashem created us differently. We have different roles, our bodies are gonna do different things. People are gonna react to our bodies in different ways.” The differences in dress for men and women have to do with biological differences and their functions, with privacy and preventing physical arousal in mind as well.

In general, Judaism’s gender roles are driven by physical differences and family. Now they are less clear cut, but traditionally they were divided into women raising children and guiding the households and men providing for the family and fulfilling community religious obligations. Western culture tends to place significance in financial success and career power, so with this lens, yes women would seem second class in Judaism, but why not value spiritual fulfillment and raising the next generation?

“The home is the central part of Judaism,” says Chani Sosover. That doesn’t mean women can’t be involved in shul, but when women aren’t counted in a minyan, it’s because they have something even more important to do. All Jewish women, including those that don’t have kids, are considered spiritually holy and have inherent beautiful qualities. The problem girls face with tzniut goes beyond clothing restrictions and is really about trying to reconcile with the role women have in Judaism. If every girl understood her value and what the Torah really says about women, many more people would realize the beauty of tzniut.