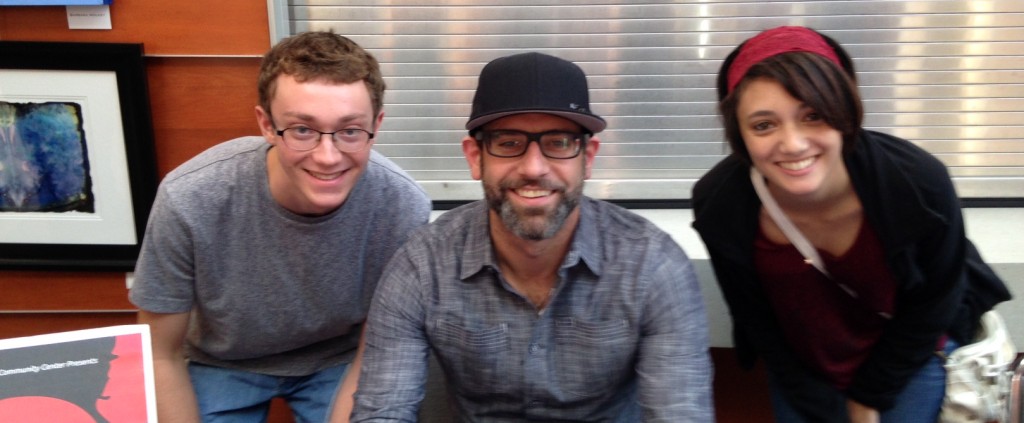

Slider image courtesy of the Bronfman Fellowship.

“What is Judaism?”

This question was posed to me by our Head of School Adam Tilove when I sat down with him to discuss how pluralism operates at Hyman Brand Hebrew Academy (HBHA). I was at a loss for how exactly to describe it. In the most technical definition it is an ethnoreligion, but that definition is too narrow in scope for a vibrant culture spanning centuries, people, and continents.

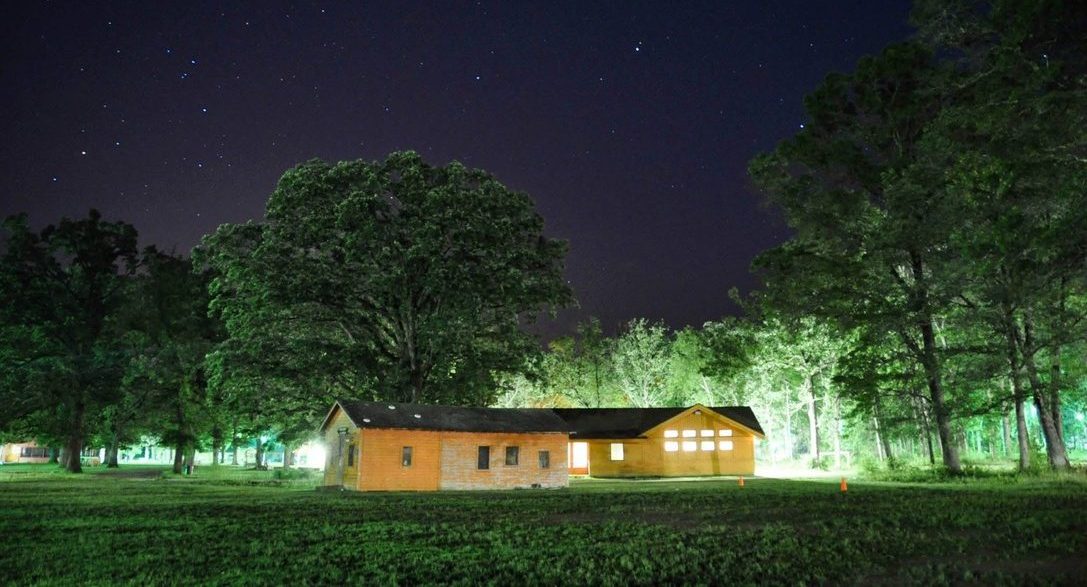

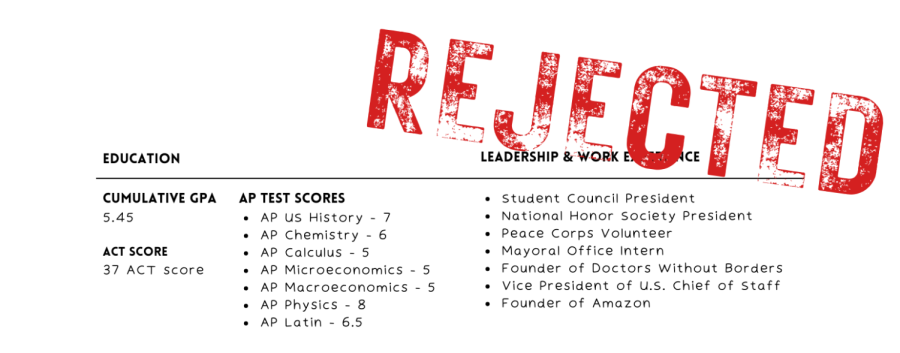

The inspiration for writing this article comes from being accepted into the Bronfman Fellowship this past spring, which takes 26 Jewish juniors from diverse backgrounds across the US and Canada on a month-long trip to Israel (or in my case rural Connecticut because of COVID-19 mitigation measures) where fellows undergo text study of both Jewish and secular sources, building a pluralistic community.

It sounds awfully familiar to the purpose of a certain Jewish day school.

So why attend this prestigious program if what they offer is what I have here in Kansas City? The main appeal for me was traveling somewhere new and unknown, and to meet other Jewish teenagers like me wanting to bridge differences and learn together rather than grow stubborn and hard-headed in our ways of practice.

It is hard to believe that I am still in the midst of the fellowship year because this past summer was one of the greatest experiences of my life. It was at Bronfman that I truly learned that the goal of pluralism is, in fact, achievable. Even if my thoughts on what pluralism actually is has changed.

According to Tilove, HBHA “need[s] to reflect the diversity of thought and belief of the Jewish people. That’s what being a pluralistic school is.”

This emphasis on pluralism is important because it acknowledges the many different ways a person can practice Judaism, and not only acknowledge, but validate them. For me, Bronfman was exactly what I needed in my development because of my own struggles with my Judaism. The culture and history are easily accessible to me. Judaism as a religion is where I start to lose my certainty and confidence. Yes, I’ve had over a decade of Jewish studies education, will gladly lead a morning prayer service, and I can discuss the details of the story of Reish Lakish and Rabbi Yochanan. But my thoughts of the existence of G-d? The thought has never really crossed my mind. It seemed as if it was always a non-question and not worth spending the time discussing when there is halacha to study.

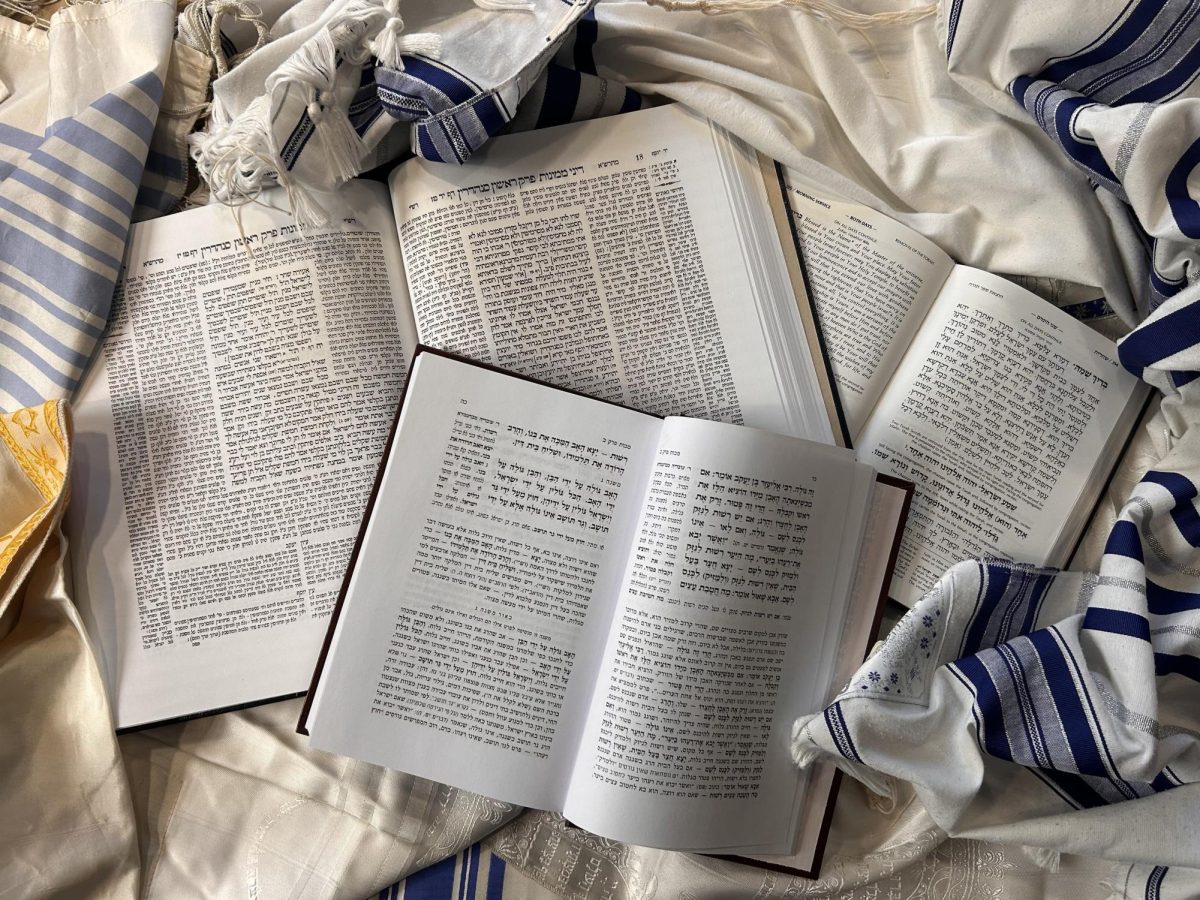

But then comes Bronfman. The entire premise of the program is dedicated to learning for the sake of learning. Where I became lost was learning Jewish law for the explicit purpose of learning Jewish law. There was no intention, no deeper meaning, no existential crisis to navigate through. Questions and topics that I would have never thought to learn about were what we spent our time doing. Whether reading Talmud on what intersex people are liable for, or studying Franz Kafka’s journals on notions of Paradise, a whole new world of Jewish living and learning was opened up for me.

Admittedly, the aspect of text study would not be nearly as appealing if I did not have a cohort of wonderful individuals whom I love dearly, disagree with frequently, but would nonetheless not trade for the world. Getting to meet people from such varying backgrounds different and similar to your own and given nothing but the gift of time to get to know them is a blessing.

This is not to say that pluralism is easy. In fact, it is quite the opposite. So many issues arise that are much too numerous to list in one article. Eliana Schuster in her 2017 article for RampageWired, also on the topic of pluralism came to the same conclusion as I did: There certain divisive issues where bridging the gap just is not possible. Some people will be left uncomfortable and feeling like they are not seen. I know there were periods both at HBHA and at Bronfman where I felt like I did not belong. I was calling my own personal Jewish identity into question and forcing myself to believe that my expression of Judaism is not valid in its own right and that some secret aspect was lacking. It is an insecurity that I am still working through to this day.

“Before Bronfman, I have had this critical problem in being a religious Jew,” says Ephraim Shaulnov, a 2021 Bronfman Fellow from San Francisco, CA, in the same cohort as me.

“Judaism inherently has a prerogative to be inquisitive…and the way I was raised, I never fit into a broader Jewish community because of that. Bronfman was the first place I went to where [Bronfman] didn’t click for anyone, and that clicked for me.”

In a sense, there is an equality in everyone being a little bit uncomfortable, regardless of the reasoning behind it. If everyone felt fully in their element, there would be no breeding ground for discourse. Even if it was unproductive, at the very least, there was dialogue and a conversation to be had. There is intentional tension built into the foundation of a pluralistic community that allows for better appreciation of differences between people, even if there cannot be any reconciliation.

“At this school, we are in contact, and sometimes in conflict, with how we use our resources,” says Tilove. “These things are all intentional. You see it in what the dress code is, what the kashrut policy is, whether we can assign homework or tests during holidays. It’s a balancing act.”

Pluralism is not meant to be a perfect framework where everyone is left feeling satisfied. It’s simply not possible to make everyone happy and content. There have been days where I myself am ready to give up the pursuit of a Jewish education in its entirety because of the frustration I felt that it was just not possible to achieve a meaningful Jewish studies experience while being exposed to new ideas and simultaneously not having to hear thoughts I don’t agree with or learn in ways that feel unapproachable.

In part, the process of writing this article is figuring out what I want. I suspect I will not arrive at any decisive conclusions anytime soon. That’s the way it should be. Pluralism is flawed in its goal of coexistence between multiple bodies of people. The flaw is deliberate in design with its purpose of leaving individual parties unsatisfied because it promotes conversation, deliberation, and disagreements: the ever-elusive art of conversation, if you will. What is so deceiving about conversation is that in the seemingly innocent act of talking to another human being and engaging them, entire worlds of opinion and thought are being created and destroyed in the span of a few minutes. Notions and prejudices are made at the utterance of a simple “hello.”

In an era of polarization, we make judgment calls about people from first appearances. It’s part of the human condition. An “us versus them” mentality is easy to fall into when feeling attacked, but it is harder to break. I know this is the case for me, both subconsciously and consciously. But the hidden beauty behind pluralism is in its many applications. Secrets about people you think you have figured out are revealed behind a simple question. It is easy to get caught up in one’s own life and in the material world that commands our full attention. And for the briefest of moments, Bronfman removed me from this world and helped me rediscover the appeal behind finding out what makes a person tick; even if they’re fundamentally different than you in every way. In writing this article, I hope to remind myself and you, dear reader, that it is never too late to press pause on the chaos of daily life, and have a chat, banter, or parley with people closest in your life, as well as those you’ve yet to meet. You’d be surprised at the complexities that lie just beneath the surface, waiting to be expunged. And though the answers you find (or lack thereof) may not be satisfying, isn’t worth the effort to try?

“What is Judaism?”

To never stop seeking. To never be still. To never be satisfied.

“Ben Bag Bag said: Turn it over, and [again] turn it over, for all is therein. And look into it; And become gray and old therein; And do not move away from it, for you have no better portion than it.” -Pirkei Avot 5:22