What Can We Learn from Observing Shabbat?

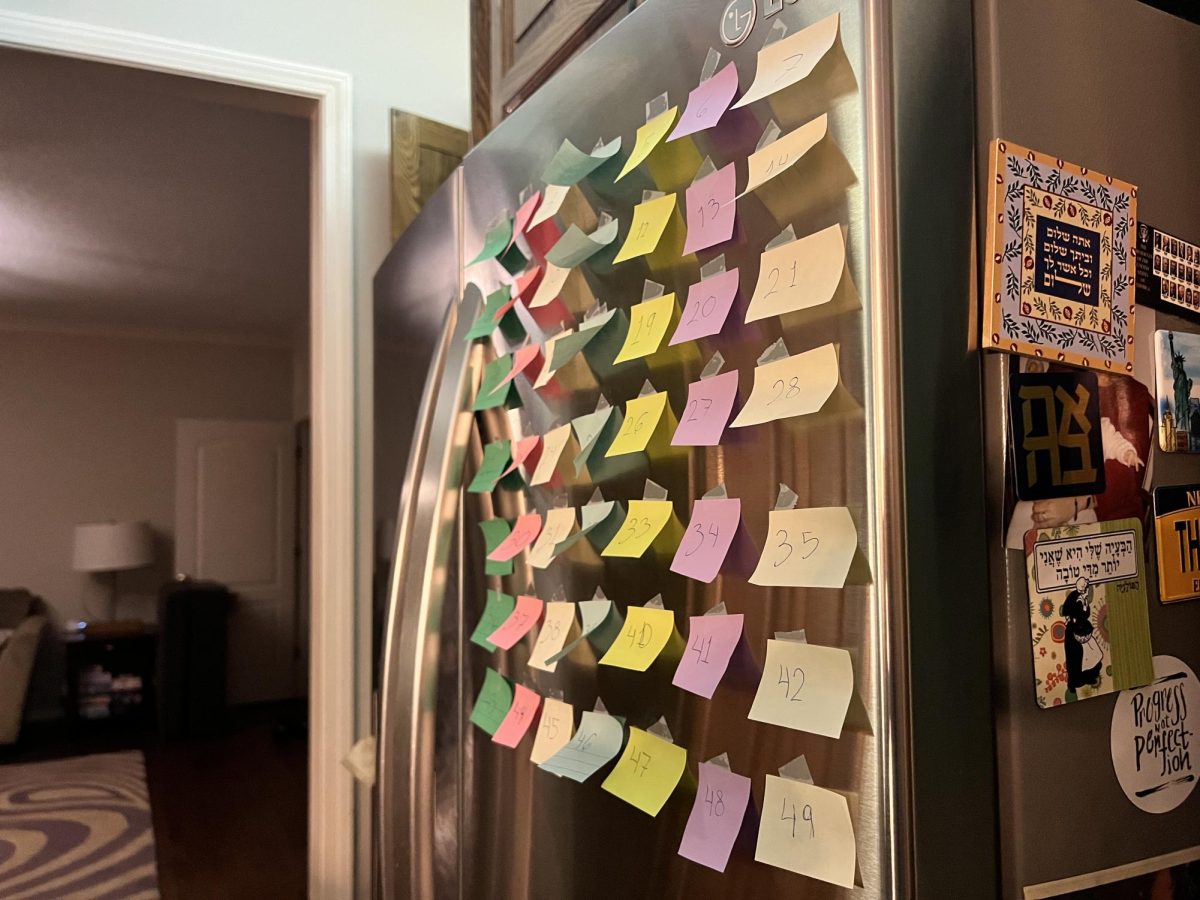

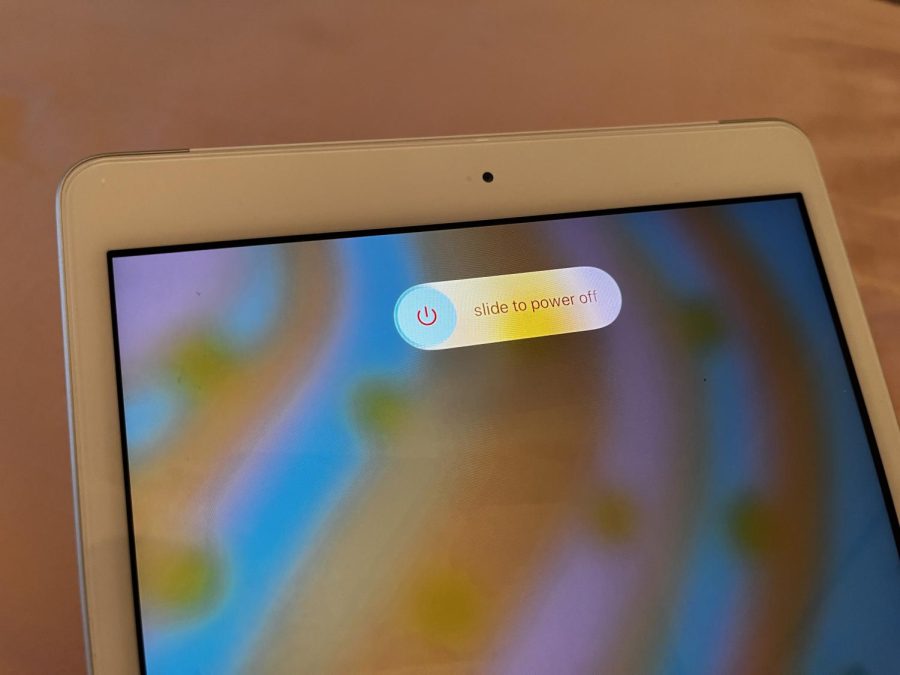

While disconnecting from our devices may be difficult, on Shabbat many find it peaceful. Photo by Annie Fingersh

February 10, 2023

In a world dominated by technology and the need for productivity, Shabbat is the one day of the week where Jewish people can truly disconnect from their secular lives and simply “exist.” What can we learn from observing this sacred holiday once a week?

While some don’t gravitate towards observing Shabbat because of the restrictions on certain tasks, meaning can be found in these laws. Rabbi Elizabeth Bonney-Cohen, Hyman Brand Hebrew Academy’s (HBHA) Rabbi for Outreach and Family Engagement, speaks of how much she values the laws of Shabbat. She says, “By controlling some of my behaviors, not cooking, not driving, not being on my phone…it frees me up to…enter into a different relationship with time and slow down.”

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, a leading Jewish theologian and philosopher of the 20th century, is widely known for referring to Shabbat as a “palace in time” where one can disconnect from everything else in the world and appreciate those sacred 25 hours. Rabbi Bonney-Cohen notes the significance of being separated from her daily life on Shabbat. She says, “When I light Shabbat candles, I resign myself to whatever I didn’t finish. [I know] it will be waiting for me [after Shabbat].”

HBHA Junior Ellie Glickman shares this sentiment: She discusses how relieving it is to be able to set her worries aside on Shabbat and know that they will work themselves out in the end. “We spend the whole week trying to further our…agendas, but then…[Shabbat] is an opportunity to be introspective,” Glickman says.

Heschel says, “Six days a week we wrestle with the world, wringing profit from the earth; on the Sabbath we especially care for the seed of eternity planted in the soul.”

Both Glickman and Rabbi Bonney-Cohen share this sentiment on how peaceful Shabbat can be if you simply let go. Glickman says, “I don’t have to get better…on Shabbat I have this day where I’m just living in the present, and I’m not trying to better myself, I can just exist.”

Rabbi Bonney-Cohen says, “All week long we’re told that our worth is contained in a sense of what we can produce, and on Shabbat it’s just about being enough in and of ourselves.”

While one of the blessings of Shabbat is to be able to reflect on yourself, it is also a time to connect to other people in a way that’s not possible during the week. Rabbi Bonney-Cohen notes that while Shabbat is about self, it’s also about connecting with people and our community. Truly being present and having meaningful conversations is difficult in weekly, secular life, so Shabbat is a set time to disconnect from everything else and engage with one another.

While Rabbi Bonney-Cohen practices Shabbat in a traditional way, she notes that to experience Shabbat and connect to it, you don’t have to celebrate traditionally. She says, “I’ve had plenty of meaningful Shabbat experiences with people who don’t have a traditional Shabbat practice.” The spirit of Shabbat can be captured simply by having people over for dinner and being present together or talking about deeper topics that you normally wouldn’t.

While people may practice Shabbat differently, it can be a beautiful “palace in time” to let go of the world around you, to connect with others, and to connect with yourself.