Understanding and Healing Internalized Antisemitism

March 24, 2023

I, like many HBHA readers, grew up inside of the “Jewish bubble.” My whole life I went to Jewish day school, summer camp, and regularly attended synagogue. I have participated in countless combating-antisemitism workshops, lessons, and seminars, but one conversation that is never brought up is the antisemitic rhetoric within Jewish circles.

This phenomenon is known as internalized antisemitism. Internalized oppression, a phrase used to describe the beliefs and behaviors marginalized people have been socialized to accept, has been a social justice term since the 1980s.

Director of Education and Programs for American Jewish Committee – Jewish Community Relations Bureau (AJC-JCRB), Sarah Markowitz, describes antisemitism as the oldest hatred. She says it is rooted into “societies worldwide, including our own here in the United States.”

Markowitz says antisemitic tropes such as stereotypes about Jewish wealth, power, and greed perpetuate antisemitism, the oldest form of hatred. She says that these stereotypes create “what people think Jews are.” She said that it is natural for young Jews to grow up hearing this rhetoric and use it to form their identity subconsciously.

One way that AJC-JCRB helps tackle internalized antisemitism is through the national Leaders for Tomorrow (LFT) program. LFT chapters are run in Atlanta, Chicago, Detroit, Kansas City, Los Angeles, Long Island, Miami, New England (Boston), Washington, D.C., Westchester/Fairfield, and New York City. The teen leadership fellowship focuses on strengthening Jewish identity and education on combating antisemitism.

I posted on Instagram about internalized antisemitism to see if other people were going through a similar experience and asked if anyone wanted to call to discuss this issue. Four other juniors responded: Ezra Gussin (Northbrook, Ill.), Sophia Lamin (Eagan, Minn.), Ari Birnbaum (Upper West Side, NY.), and Emma Rosenthal (Overland Park, Kan. and fellow HBHA junior), and we scheduled a Zoom call.

Gussin described a moment when he missed school for a Jewish holiday, and his Jewish and non-Jewish friends teased him saying, “Oh! You’re Jewish!,” “Oh! You’re religious!” He said with a laugh that after that encounter it makes him wonder, “is there a right and a wrong way to practice your religion?”

Birnbaum shared this sentiment of receiving judgment from different denominations. He described a setting in a more orthodox environment where the other teens gave him “side eyes, and weird looks.”

Lamin then described conversations in her English class about Shylock in the Merchant of Venice and Meir Wolfshein in The Great Gatsby. Both of these characters are Jewish caricatures and Lamin was furious with the lack of conversation about the harm these representations cause. She said, “I felt like it [the explicit antisemitism] wasn’t pointed out enough in that sense.”

Gussin responded to Lamin’s lament saying if this media was talking about other minorities “would there even be a discussion of ‘oh is this racist?’ or would people just say ‘yes this is racist.’”

Throughout the interview, the students emphasized their Jewish pride.

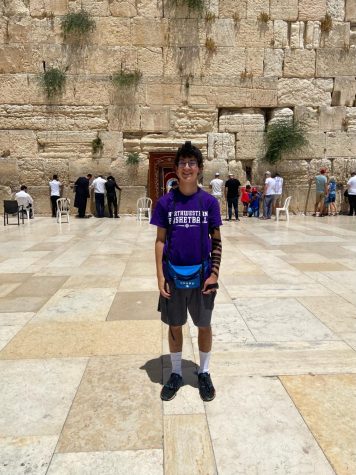

Gussin shared that one time when he felt proud of his Judaism was at the Kotel, or Western Wall, in Jerusalem. The experience reminded him of his ancestors who stood in the same place and it made him “proud.”

Rosenthal described her educational journey preparing for her Bat Mitzvah when she realized that Judaism is what she connected with and these practices were therapeutic.

“One piece of Judaism [I really connect to] is the community aspect of it,” Lamin said. She described driving down the street in December and seeing Hanukkiahs in the windows, and “feels some sort of kinship with them.”

Birnbaum called this a cultural claim. He describes his connection to Judaism as integral to his identity. “If you know me, then you know I’m Jewish,” Birnbaum said.

Judaism has always been the key component to my identity, so reaching teenage years and seeing that it was a trait people were ashamed of was traumatizing. Finding confidence to participate in Jewish practices and leadership is still something I struggle with.

My conversation with Sarah Markowitz was truly enlightening as I learned about the generational programming that built this insecurity. Also, seeing the other teens who were cognizant of this issue made me feel entirely less alone. I felt so validated when talking to Gussin, Lamin, Birnbaum, and Rosenthal, and I hope that readers will feel inspired to reach out to their Jewish peers to talk about their shared identity.

Sharing moments of pride will help heal the internal turmoil spreading throughout the Jewish teen community. We need to fight antisemitism with Jewish pride, especially when this hatred is coming from ourselves.