What’s Wrong with Fast Fashion?

February 16, 2022

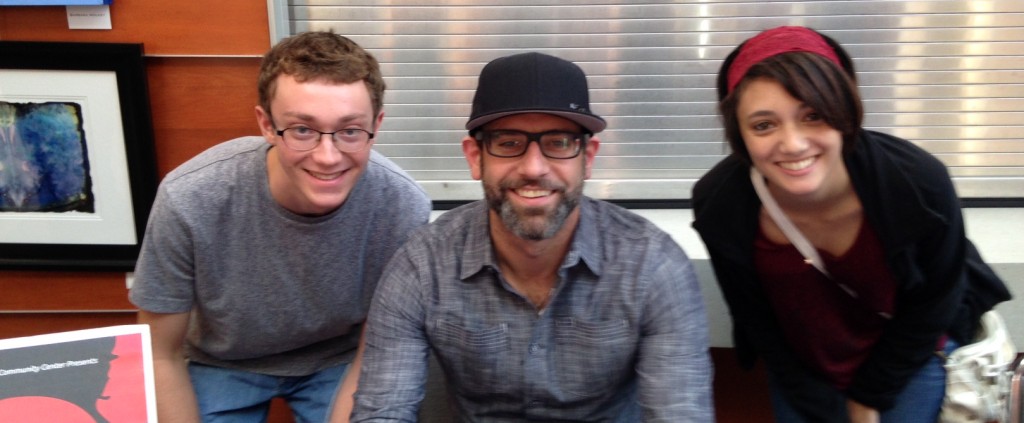

Image by Annie Fingersh.

I am held captive to fast fashion and the entire fashion industry. I enjoy shopping for the newest clothes and biggest trends at a price that won’t max out my debit card. I get emails from my favorite stores that send me coupons and urge me to buy items from their weekly drops. I indulge myself in buying clothes for fun, amassing so many items that I end up wearing them a few times before donating them again. Did I say “I”? I meant “we;” I meant society. We are held captive to the vicious cycle of fast fashion.

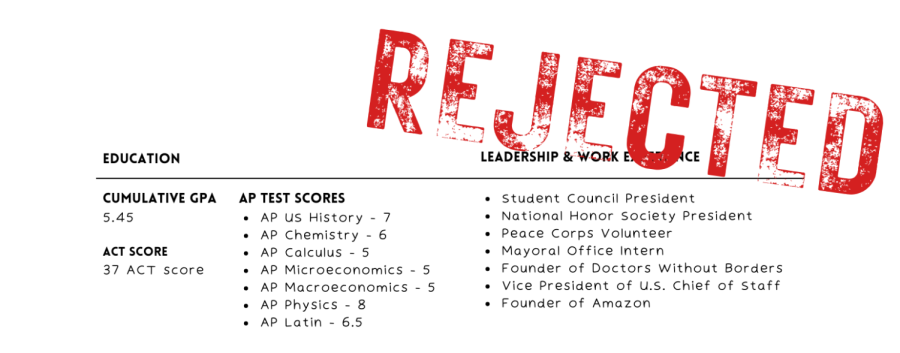

But what exactly is fast fashion? The industry of fast fashion first gained popularity in the early 2000s when stores pulled trends from high end designers and mass produced them quickly and at low costs. As shopping often became mainstream and easier, and especially with the advancement of online shopping, fast fashion became one of the most profitable industries in the world. Sounds great, right? Cheap, trendy clothing? Wrong. Fast fashion affects everything in our world ranging from environmental turmoil to employee mistreatment.

The cycle of fast fashion is, as the name implies, fast. Once designer brands and celebrities make a new style popular, the biggest chain stores in the world replicate the trends, produce items quickly, and sell them cheaply. The lifespan of fast fashion items is laughably short; typically, an item will be worn a few times and then discarded, accumulating in our landfills.

Stores that once produced four collections per year (summer, fall, winter, and spring) now produce about one new collection per week or every other week, growing profits exponentially. But this isn’t a one-sided problem: as fast as companies produce merchandise, consumers buy it, continuing to drive the cycle.

Since the fast fashion industry is concerned with churning out as much merchandise as they can, this results in low quality clothing that is made at rapid speeds, often by employees in third-world countries who are being underpaid and mistreated. According to data from MinimumWage.org, the average minimum wage for garment workers around the world is $470 per month, with some earning as little as $26 per month. These are not liveable conditions, not to mention the unsafe, filthy factories they work in. Many garment workers even develop physical maladies due to the fast pace, bad conditions, and exhausting components of the work.

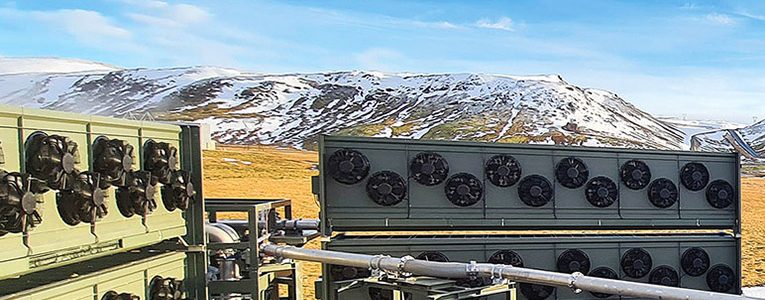

Another big impact of fast fashion is on the environment. For a society that is so sensitive to and cognizant of climate change, most people are comically blasé about the fashion industry’s impact on our environment. According to Business Insider, 85 percent of textiles end up in landfills, and every second, a garbage truck full of clothing is either burned or dumped in a landfill. The fashion industry is one of the biggest industrial contributors to pollution in the world, accounting for about 2-8 percent of carbon emissions as well as being the second largest consumer of water worldwide.

Junior Aviva Clauer says that she chooses not to support fast fashion because of “the impact [of it] morally and environmentally,” and that if people continue to support it, there is no possibility of ever ending this cycle. Clauer says that she does not want to support companies that “involve themselves in child labor or unpaid labor of any kind.” She also mentions that “it’s difficult to know what your individual impact is,” but it is important to her morally.

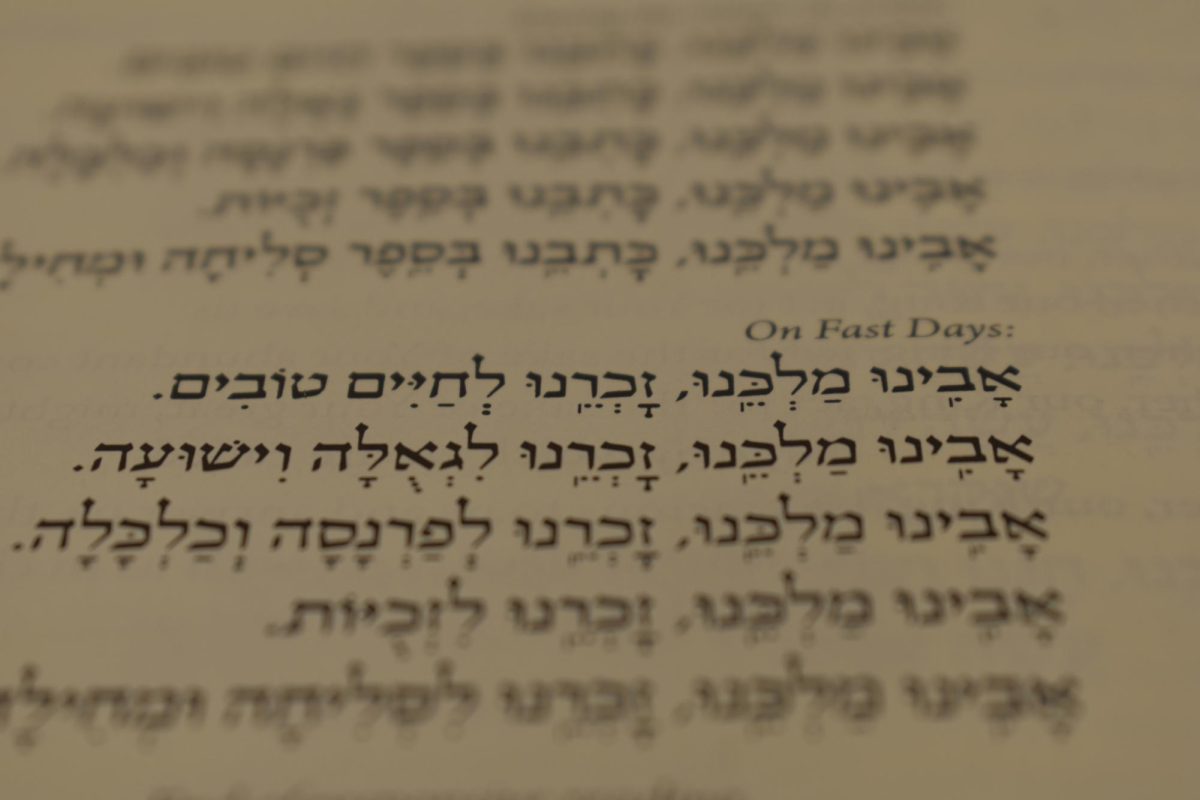

Through a Jewish lens, it is also imperative to be conscious about what we purchase and how those purchases affect the world around us. The Jewish concept of Tikkun Olam, or repairing the world, is a cornerstone of Jewish ethics and an important consideration when choosing to support fast fashion. The phrase comes from the Mishnah and Kabbalah, and in the times of creation, Tikkun Olam was meant to separate the holy world that God created from humanity’s sins. Today, it is associated with social responsibility and helping to fix what is wrong with the world, like being a mensch to help improve our society for all people. Actively choosing not to support fast fashion is just one part of Tikkun Olam, one step on the path to repair our world.

So, what can be done? Aside from businesses and huge corporations making big changes to their policies and the way they operate, we as consumers can do more. We can buy second hand and at thrift stores, because even if people donate clothing to thrift stores, about ⅔ of unbought apparel ends up in landfills, which was about 11.5 million tons in 2017. For people looking to buy designer and luxury items, there are even high-end second hand stores that can be supported. And if thrifting isn’t your jam, you can always buy sustainably made and environmentally conscious clothing from brands like Patagonia, Sezane, and Whimsy+Row; brands that use recycled or organic materials and significantly less water for clothing production. Similarly, Clauer chooses to buy sustainably if she is able to, or she also thrifts clothes.

While choosing to not support fast fashion is an admirable choice, it is also quite difficult. Clauer says that, “nobody is perfect,” and “nobody can 100 percent refrain from supporting fast fashion, but pushing back on it as much as you can… to whatever degree, is influential and important regardless.”