One of Hyman Brand Hebrew Academy (HBHA)’s unofficial requisites is that by the time a student receives their diploma, they are well versed in the prayers of the siddur (prayer book). This way, the student is able to speak the shared Jewish language–the words and melodies of traditional Hebrew prayers. HBHA students know most of their daily prayers verbatim and by memory. They would be perfectly capable of stepping into a synagogue in a foreign country, opening their siddurim, and joining the congregation in Hebrew song, silent prayer, or meditation.

There are, however, problematic aspects surrounding the HBHA upper schooler’s relationship to and knowledge of prayer. Yes, they can recite the Shacharit blessings with their eyes closed, and they probably have a steady grasp on their literal translations. Yet, in all likelihood, they can not identify the source of the prayers.

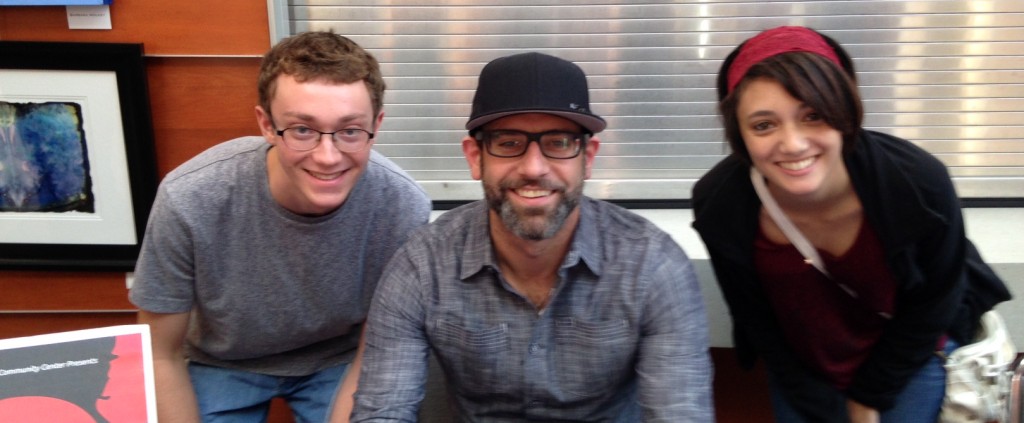

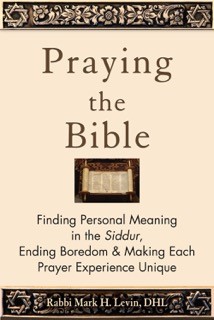

Rabbi Mark Levin, the founding Rabbi of Congregation Beth Torah in Overland Park, Kan., explored these realities of the HBHA upper schooler’s prayer literacy with them during a mentoring session during the fall semester 2016. Levin recently published “Praying the Bible,” in which he guides his readers through his ideas on ways in which they can find personal meaning in daily prayer. Levin’s conception of the siddur as an intertextual collection whose embedded Biblical quotes can elicit meaning for the one praying sparked the interest of several students. Junior Eliana Schuster searches for alternative forms of meaningful prayer in her Upper School Student Council (STUCO) committee on tefillot, and she was particularly curious about Levin’s approach.

“I never thought of the way prayers were put together,” Schuster reflected. “I liked that approach and want to use it as a way of finding meaning in prayer.”

Rabbi Levin explained to the upper schoolers the structure and history of our siddur and the ways in which we might derive value from a deeper understanding of them. The siddur, which Levin calls “embodiment” or “home of Jewish prayer,” can be read literally. For some people, the literal translations of the siddur’s words are enough to provide a spiritual prayer experience. For others, analyzing the context in which the prayers embedded by the Rabbis around 90 CE appear in their original biblical sources can add newfound import.

Levin cited one of the most widely known quotes of the Amidah in order to exemplify this thought. As we begin to recite the Amidah (the central part of a prayer service), we say these words together:

“Adonai S’fatai tiftach, ufi yagid tehilatecha,” which can be translated into meaning: “My God, open my mouth and my lips will proclaim your glory.”

A sensical way to begin a series of prayers, is it not? “A logical, clear, but superficial understanding of the words,” Levin remarks. Preparing to invoke the 19 prayers of the Tefillah, or Amidah, we request that God will hear our prayers and open our mouths.

“Why did the Rabbis insert that phrase as an opening?,” he asks–and proceeds to promptly answer his own question.

“The whole Tefillah is a replacement for sacrifices. We’re transitioning in the year 90 [C.E.] to the removal of sacrifices.” In Psalm 51, from which the “Adonai sfatai” quotation is taken, David entreats God, stating “You do not delight in sacrifice.” In place of sacrifice, David offers a “humble and contrite spirit.”

After reciting “Adonai s’fatai,” a person bows, proving their humility of spirit. “God wants humility,” Levin explains, “so the rabbis built that into the siddur.”

This lens, where both the Bible quotation in the siddur and the context from which it is pulled interact in a somewhat clandestine manner is fascinating. Still, it only addresses two of the three integral components of Levin’s equation–the third being the context of the one praying.

Levin speaks to the experience of the person praying, suggesting that prayer–rather than being a source of boredom–can exist as an opportunity to gain insight. For instance, using the example of petitioning God that he “open our mouths to proclaim his praise” in the context of King David offering a contrite spirit, we may be able to find some perspective in those words.

If I were to say “Adonai s’fatai” following a crushing defeat in a basketball game, the words “open my mouth” could suddenly signify to me the need to slow down and remember to maintain humility rather than mulling over all the things I could have done differently during the game. Simultaneously, the person next to me could utter the same words and instead reflect on an argument they had with a friend, where perhaps they should have set aside their ego and been the first to apologize. In this way, Levin suggests, prayer can be poetry.

“Looking at prayer as a form of poetry is just a cool way to think about it as a piece of art that was put together. Even if you don’t believe what it’s saying or what the author was intending, it first of all lets you appreciate the beauty of poetry but also lets you find your own interpretation because that’s what poetry is all about,” Schuster shared.

Prayer is “not designed to be done once a week. Like medication, use it as prescribed. It’s designed to be done every day…you don’t have to open a siddur. You can just sit down every day and connect with God. It’s not effective if you do it once a week. If you daven [pray] daily, you know the siddur by heart. It was designed to be known by heart so that while you’re praying you can think about the words, the quotation, and the thing in your life,” Levin asserted.

HBHA students have two of Levin’s requirements down pat–they know the siddur by heart and they come into tefillot with certain thoughts and life circumstances on their minds. However, in order to achieve a meaningful experience, it could be helpful for them to become cognizant of not only the prayers themselves, but the quotations as well. That way, they will be able to approach prayer as an art form–poetry. Foreboding as it may be, poetry–once accustomed to it–is one of the most accessible forms of self-expression. 19th century English poet Matthew Arnold contends that “Poetry is…a criticism of life; that the greatness of a poet lies in his powerful and beautiful application of ideas to life — to the question: How to live.” Ultimately, in prayer, in poetry, and in prayer as poetry, we can discover for ourselves “how to live.”