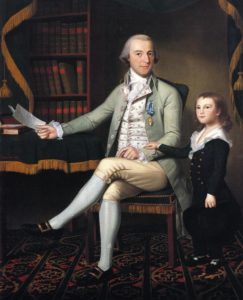

Slider image courtesy of Wikepedia.

Fiction and fact are separated by a thin line — one that the entertainment industry likes to blur. Sacrificing factual accuracy for the sake of juicy stories and high ratings is not viewed as completely unreasonable, and it’s done across the board. Historical fiction is often trusted blindly by the public simply because it’s labeled as “historical”; a dangerous trap to fall into if the fiction outweighs the fact. It is important to remember that historical fiction requires a delicate balance of fact, fiction, and a level of awareness from the consumers themselves that sometimes history, and historical fiction, leaves gaps.

In an ideal situation, historical fiction is crafted with extreme attention to detail. AMC studios’ recent TV show TURN: Washington’s Spies is just one example of historical fiction that is well rooted in fact, with little deviations throughout. The 4-season show tells the story of the Culper spy ring, a group of Patriot spies operating out of British-controlled Long Island during the American Revolution. Under the direction of Major Benjamin Tallmadge (played by Seth Numrich), the Culper ring was responsible for several military victories throughout its five years of operation (1778-1783), and none of its members were ever caught — an unprecedented feat, considering the danger of living a double life in a time when everyone was on the watch.

Only someone extremely well versed in Revolutionary War history would notice the errors in the TURN’s chronology or plot lines. As a history enthusiast and an avid watcher of the show myself, it took extensive external research to find incongruities — I did not notice mistaken accents or added personal drama until I fact-checked the show myself by reading everything from historical analysis to biographies.

My own sense of curiosity drives me to take that extra step and do the research, but I know that most people don’t feel the same way. The balance between fact and fiction is precarious when the goal is entertainment instead of accuracy. Historical fiction can’t be taken as complete fact or used as a history lesson. Rather, it can spark conversation or create curiosity where it didn’t previously exist. When used to enhance teaching, historical fiction can be quite effective as an introduction to the more accurate (albeit slightly more boring) historical studies.

My own Advanced Placement United States History class watched the show together after studying the Revolutionary War, and it allowed us to make connections and observations that the textbook alone could not cover. From writing a report on the types of coding used to encrypt messages to discussing how the lead actor, Jamie Bell, looked disturbingly similar to one of my classmates, Jacob Bell, the show allowed us to view history through a different lens.

Obviously a TV show can’t be as reliable as a history textbook or a primary document, but they aren’t made to be that way. A good historical fiction piece hinges on the individual creator’s intent as well as the history in question. TURN is only as accurate as it is because there are mountains of sources on America’s early years to help fill in the blanks and augment the hard and dirty facts of war. Not every piece has factual support propping it up, and it is in those instances where the audience has to go find the truth for themselves. Whether that means reading a book, doing research online, or finding primary sources, it has never been easier to verify information and seek out the truth.