Slider image courtesy of Instagram.

In 2017, a study was conducted by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), that showed that anti-Semitic incidents have increased 57 percent in the U.S. This phenomenon has continued through 2018 and now 2019.

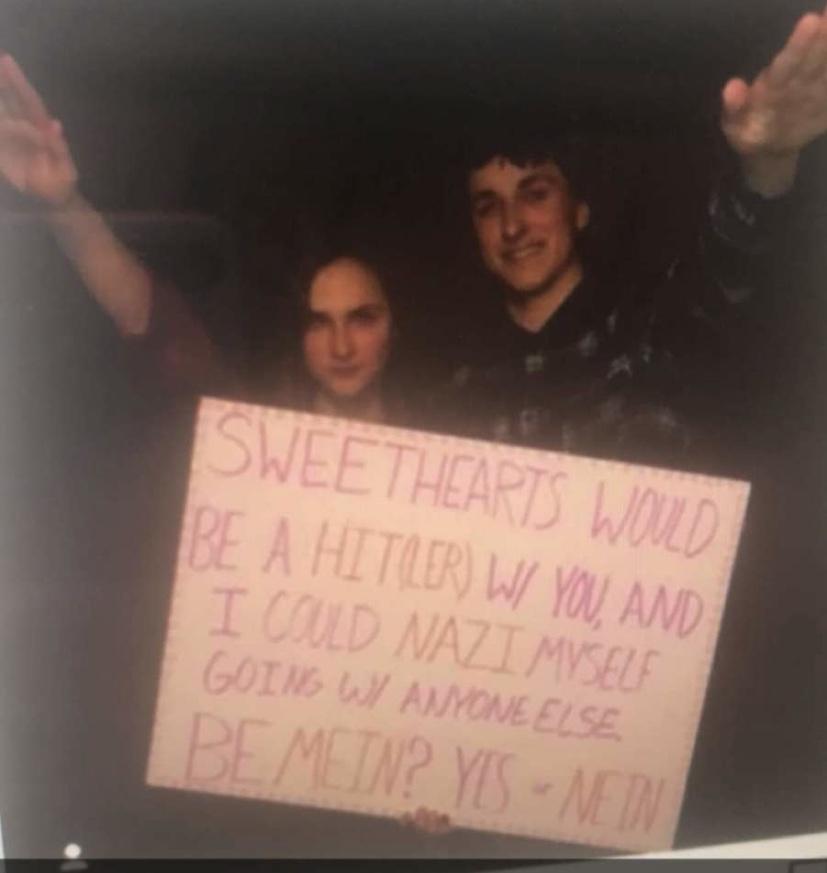

What started in Minnetonka, Minn., as a social media post has spread nationwide. The post showed two teenagers doing Nazi salutes and holding a dance proposal sign referencing Hitler. The sign said “”Sweethearts would be a Hit(ler) w/ you, and I could Nazi myself going w/ anyone else. Be Mein? Yes or Nein.”

The post was deleted but that did not stop many people from seeing it and sharing it to spread awareness. The students attend Minnetonka High School, a public school, and in a statement from Principal Jeff Erickson the students will be ‘disciplined’. But how can public schools around the nation educate their students on these important matters? What kind of punishment is appropriate? How can Jewish kids who go to that school become safe again?

On Jan. 23, Erickson announced that the students who were involved in this incident apologized. Erickson said “both students involved have……share[ed] their apologies with the school community,” and they both are “remorseful and deeply regret their actions.”

Erickson then continued to express how this impacted many Jewish people in the community, and he recognized that “the impact the posts had on [our] Jewish students, staff and [their]’ families…..and their concern for their safety and well-being.”

Ellie Keller, a sophomore that attends Saint Louis Park high school in Minn., experienced this first hand. When she saw the post she immediately thought “it was hard to wrap my mind around that kids my age thought this was a good idea, but also that they had the idea in the first place.”

Keller believes that the most important takeaway from the social media post is “that anti-Semitism still exists and is not just perpetuated by a certain generation”, and to prevent these actions from happening again we should “keep teaching kids about equality, especially when they are young.”

In Minn., teaching about the Holocaust is included in social studies curriculums for middle and high schoolers. The Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota and the Dakotas recently reported that students in Minnetonka have received education about the Holocaust and some even heard stories from Holocaust survivor Judith Meisel last year.

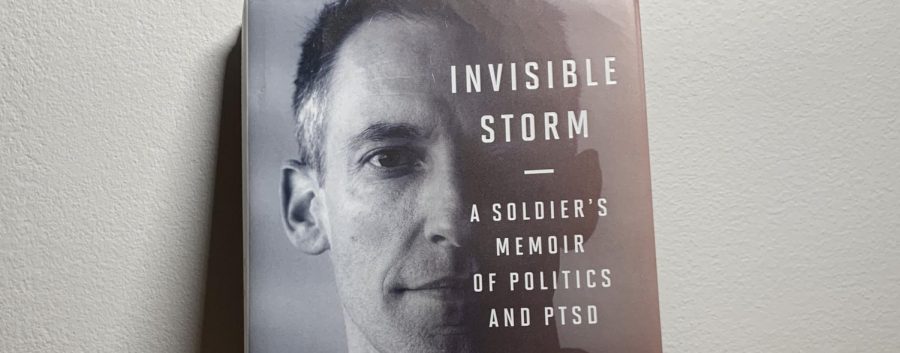

This year Keller read “Night,” a non-fiction book about Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel’s experience at Auschwitz-Buchenwald. Keller said that the book allowed her non-Jewish classmates to ask questions while the teacher answered by “not only [being] factual but also respectful to all of the students.”

But many people are not as impressed in how teachers are educating students about the Holocaust. Holocaust historian Yehuda Bauer thinks that “the Holocaust is too often turned into vague lessons of the danger of hatred or prejudice.” Talking to Holocaust survivors could be more effective than learning in a classroom by a teacher. Survivors can also provide a more personal discussion and experience for many students.

Anti-Semitism may not be near the end of its lifecycle, but for teachers to teach about the Holocaust in effective ways, like talking to survivors or watching movies that survivors have made, could make the biggest difference.