Slider photo by Ilana Fingersh.

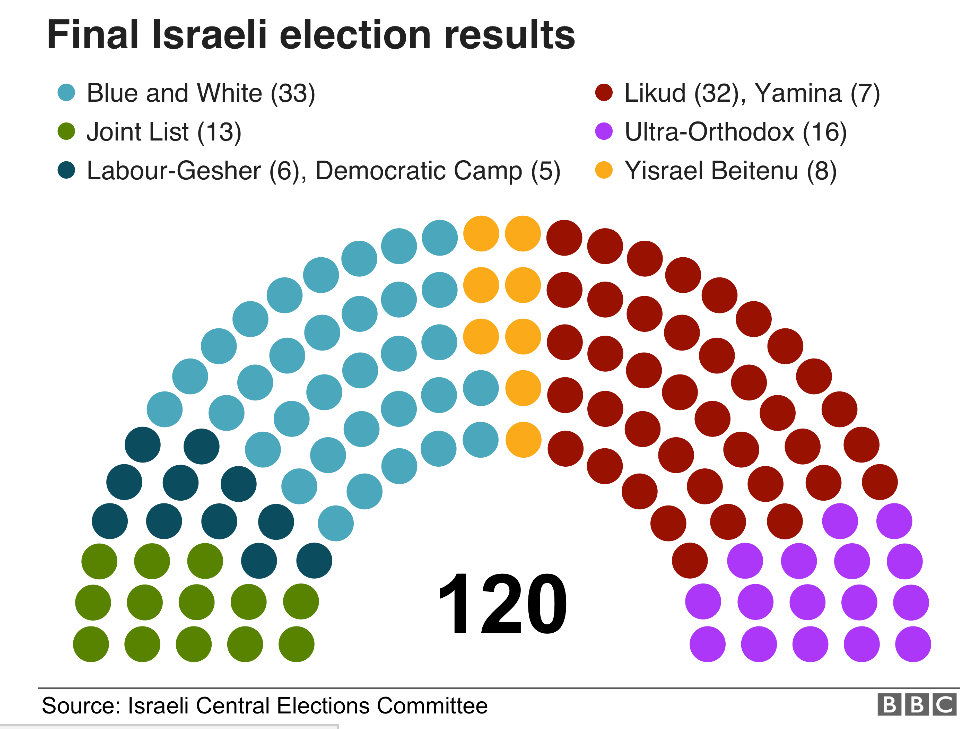

After the unsuccessful April 9, 2019 elections, Israel held a second round of voting on Sept. 17, 2019. Israeli President Reuven Rivlin originally gave Benyamin Netanyahu, the incumbent Prime Minister, the opportunity to form a government, but Netanyahu was unable to obtain a majority. Rivlin extended the offer to Benyamin Gantz, who has until Nov. 20, 2019 to put together a coalition. These elections have made history in Israel for a variety of reasons, and there could be more twists to come.

Unlike the United States, in Israel citizens cast votes for a political party, not a specific candidate. Any party that receives at least 3.25 percent of the overall vote is eligible for seats in Israel’s 120-seat Parliament, the Knesset. After the votes have been counted and the seats have been allotted, Rivlin extends the offer to form a coalition to the party that he thinks has the best chance of doing so. A coalition is 61 seats, which has to be accomplished by a leading party forming alliances with smaller parties to become the majority, typically ones with similar values.

Following the April elections, Netanyahu failed to put together a coalition. This was the first failure to form a government in the history of the country. His party, the center-right to right wing Likud, could not get the far right and religious parties to agree to form a coalition. One area of extreme debate during these elections was the service of the ultra-Orthodox in Israel’s national army.

Netanyahu needed the support of both Avigdor Lieberman, the head of an ultranationalist party, and of multiple ultra-Orthodox parties in order to put together his coalition. But both sides demanded that Netanyahu lean a certain way on this hot issue. The ultra-Orthodox insisted he let the mandate that allows them to avoid mandatory army service remain, while Lieberman wanted him to abolish it. This caused enough tensions that, ultimately, the Knesset voted to dissolve itself instead of extending the mandate to Gantz, another first in the history of Israel.

The second round of elections yielded similar results. However, this time Gantz received 33 seats and Netanyahu received 32. Even though Gantz won by one seat, Rivlin gave Netanyahu another chance to form a majority. Netanyahu once again failed, and so the task fell into the hands of Gantz. Rivlin gave Gantz 28 days to get 61 seats in the Knesset. If Gantz fails this coming Wednesday, Nov. 20th, Israel’s political future is up in the air once again.

As a third election in less than a year is exhausting, the idea of a direct election has been discussed. This would entail the citizens of Israel voting directly for either Netanyahu or Gantz, forcing the supporters of different parties to choose a side. In this case, the Knesset would rally around the winner of the direct election, allowing them to hold the office of Prime Minister. This was how Israel’s elections worked from 1996-2001, and if this option is explored it will be interesting to see the results.

As Gantz tries to cobble together a coalition, many questions remain. Will he attempt to form an alliance with Netanyahu’s party? And if so, who will be Prime Minister? Will Netanyahu’s indictment charges affect his eligibility? Will Gantz gain the support he needs from the Arab parties, or will he fail to put together a coalition?