Slider image taken from Flickr.

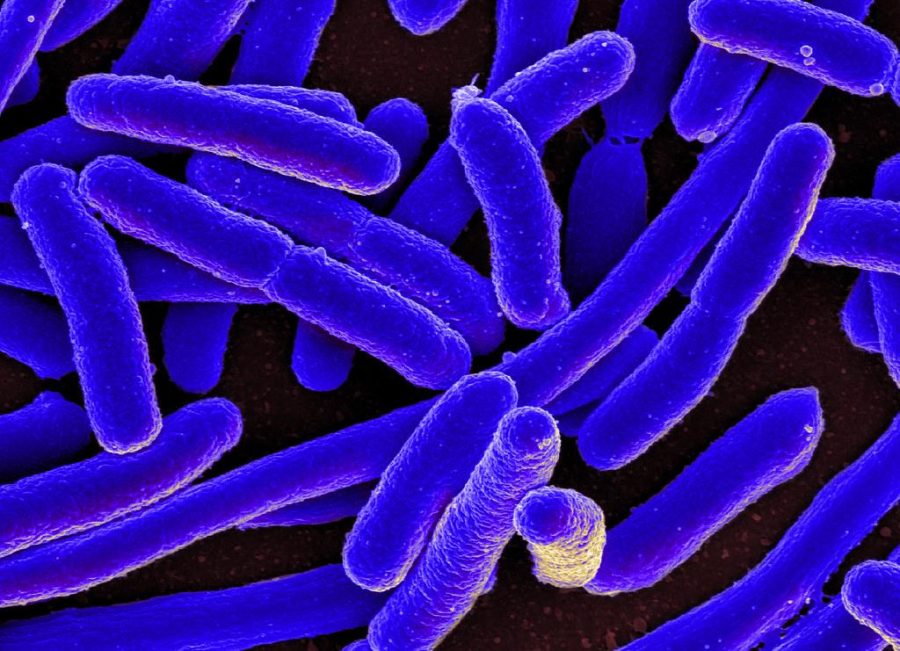

You may be asking yourself: What’s the reason for the persistent recalling of romaine lettuce? The simple answer is E.coli, but how does this potential lethal contaminant keep making its way into our systems?

E. coli is a type of bacteria that normally lives in the intestines and can also be found in some animals. Most types are harmless and can actually help keep the digestive tract healthy, while other strains are more damaging and can cause diarrhea if contaminated food or water are eaten.

It only takes a small amount of E. coli to infected a food source. Anything from ground meat and untreated milk, to animals or people, can have the contaminant. But vegetables and fruits are among the most common foods to be tainted by the strain. When manure from nearby animals mixes with water, fruits and vegetables can easily be polluted with the bacteria.

There is no clear explanation for how this toxic contaminant continues to live specifically in the leafy greens we buy nearly every day. However, constant speculation remains among scientists, farmers, and the government. If there is awareness about the failure to keep food safe for consumers, then why is extra care not taken to ensure that food is okay to eat?

“There’s no 100 percent way to make sure that they are safe,” says Science Department Chair at Hyman Brand Hebrew Academy (HBHA) Cody Welton. Although, Welton explained how petrochemicals could be used as fertilizers in place of manure, “but when you use petrochemicals as fertilizer, that takes petroleum products and that comes from oil.” In many situations, “there are problems associated with any fertilizer,” which is why it is so difficult to avoid bacteria in vegetables all together.

However, when public health is at risk, even something that is nearly unavoidable needs us to work towards some sort of solution. A simple infection from a strain of E. coli “can make people really sick, sick enough so that very old people, very young people, or people with compromised immune systems can actually die,” says Welton.

Unfortunately, unlike other illness outbreaks, E. coli has persistently infected people worldwide for years. Senior Addie Brand was infected with a strain of E. coli a couple of years ago in Mexico, but from something other than a leafy green. Approximately two days after eating what seemed to be raw fish, “[he] started getting [his] first symptom,” explains Brand. He experienced common symptoms of E. coli although they were intensified and landed him in the hospital.

E. coli can be a completely treatable infection. However, when a bacteria becomes lethal to so many people repeatedly, what’s next? Will steps be taken to ensure the safety of food, or will there be outbreak after outbreak? Something as simple as washing food an extra time can make a difference, but that is only true in some scenarios.