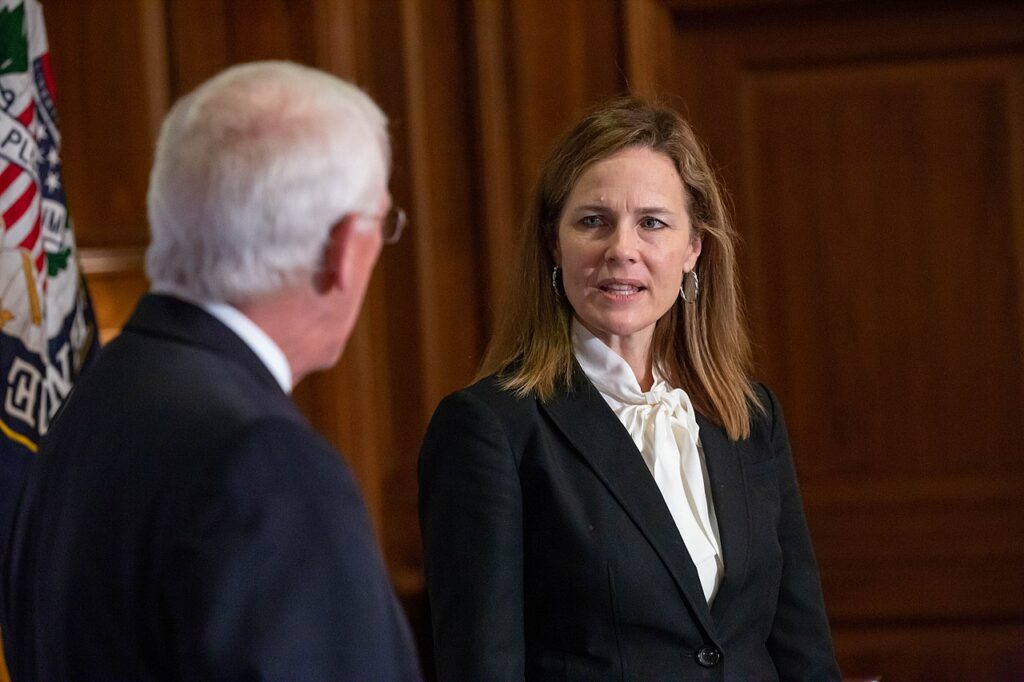

Slider from Wikimedia

Just eight days before the presidential election and only one month after the passing of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Amy Coney Barrett was confirmed as a Supreme Court justice. There has been much speculation about the circumstances in which Barrett was nominated and confirmed, but the biggest question is: What does Barrett believe in?

During her confirmation hearings, Barrett was asked numerous questions from senators including her thoughts on previously argued Supreme Court cases, especially ones that have lasting impacts on millions of Americans. It was more than just alarming that Barrett refused to answer most questions, explaining that they were hypothetical and therefore she could not give an accurate answer.

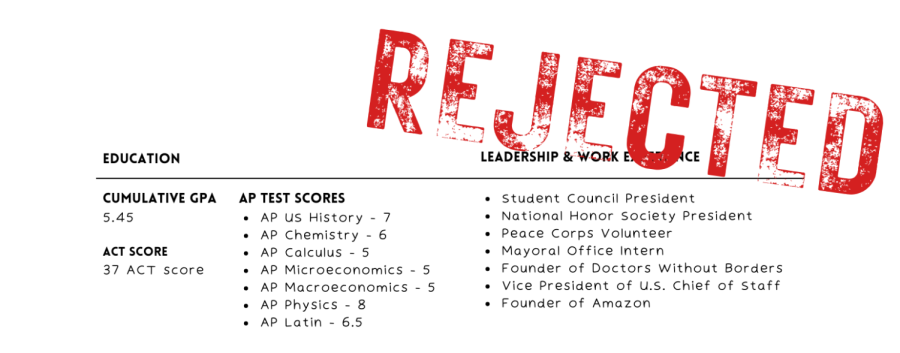

When faced with questions about previous rulings, she avoided answering by explaining that she would have to look into the cases more to give a concrete answer. The problem with this, though, is that she absolutely could have researched those pre-existing rulings, as she is allowed to bring notes or textbooks into her hearings. But other than failing to answer these questions, she was not able to answer questions that any AP government student could, such as, what are the five freedoms in the First Amendment?

Just from the confirmation hearings, Barrett’s views are extremely ambiguous. Some may know that she is an originalist– a judge who interprets the constitution the way it was viewed by the framers and the American public at the time of its creation. So what does Barrett truly stand for, and why might this interpretation of the constitution be harmful?

Here are a few cases she has argued in the past:

Though Barrett claims to be an originalist who sticks to the direct text of the constitution, many previous cases that she judged indicate that she is still quite biased.

In the 2019 case of McCottrell v. White, two incarcerated men were severely injured after officers fired “warning shots” to break up an unrelated fight. The case was taken to court under the Eighth Amendment prohibition of “cruel and unusual punishment.” However, Barrett voted against the injured incarcerated men, arguing that not enough evidence had been brought despite the testimonies, video proof, and medical records.

Speculators have also looked at Barrett’s record as a judge in addition to her work outside of her judicial career. Between 2015 and 2018, Barrett served on the board of trustees for a system of private Christian schools, called the Trinity schools. These schools openly denounce gay marriage, citing in their website that marriage is a “legal and committed relationship between a man and a woman” and they believe that “the only proper place for sexual activity is within these bounds of conjugal love.”

This language has been a part of the school’s mission both before and during Barrett’s time served on the board, and it is clear that even if she does not openly align herself with this ideology, she tolerates it. Though Barrett did not speak on her views on LGBTQ+ marriage during the hearings, specifically the ruling of Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) on same-sex marriage, Barrett’s previous position on the board and tolerance to anti-gay rhetoric and policies has been a concern of the LGBTQ+ community.

A trend in courts is the doctrine of stare decisis, or “let the decision stand.” This doctrine relates to precedent as courts generally base their arguments on previous cases and precedents. Though siding with a previous decision is not enforced, courts often try to engage with established precedents, especially of their own, to avoid overturning or contradicting subsequent cases. But Barrett takes a much different view on this courtroom approach.

In a 2013 law article, Barrett argued that “it is unrealistic to think that the Court should give its constitutional precedent more weight than it currently does,” explaining that stare decisis is already given too much power. Though she does discuss the notable point that stare decisis forces justices to think more critically about their actions when they are considering overruling a decision, Barrett fails to recognize the legal mess that comes with overruling. Putting aside the constitutionality or morality of any given case, Supreme Court decisions have an immense influence on other courts, and by overturning precedents, they also make a mess of cases that were decided based on those precedents. Though Barrett is right in the fact that in certain cases there is the need to overturn precedents, this article gives insight into the possible indifference to the importance of stare decisis and the potential for influential precedents to be overturned.

So, what of Barrett’s decisions have been deemed good?

In many of her arguments, Barrett has voiced opinions that protect the Fourth Amendment right that requires warrants for “search and seizure.” In the 2019 case of U.S. v. Terry, Barrett ruled that the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) had overstepped a man’s rights by searching his apartment without a warrant and without his consent, only the consent of his mother who was in the apartment but did not live there. Because he, as the owner of the apartment, was not there, Barrett ruled against the DEA as they had no warrant and did not check to see if the woman lived there (and evidently, didn’t notice that a woman opened the door of a man’s apartment).

In all, it’s clear that the new conservative majority on the Supreme Court can lead to a much different era of court rulings. Barrett has already begun delving into her judicial duties, and is in the process of judging her first case, Fulton v. City of Philadelphia. Especially with cases like this one, which balances religious freedom and human rights, it will become increasingly clear where Barrett truly stands. And as she is exposed to more and more cases, it will indicate her ideological positions for her future judicial career.