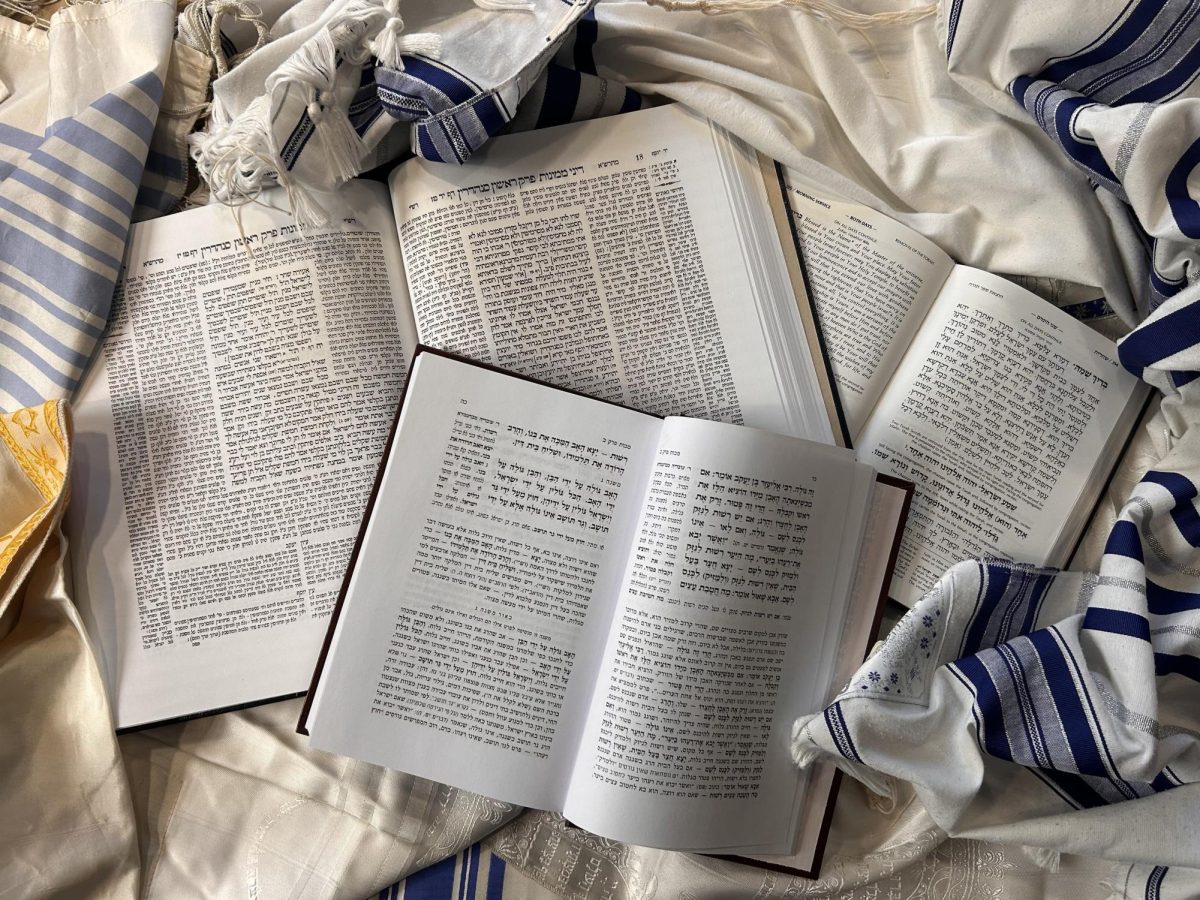

Slider image by Sagi Rudnick.

The official mission of the Women’s March is to harness the political power of diverse women and their communities to create transformative social change. But in practice, does this commitment of inclusion truly apply to all? Not really. Anti-Semitism emanates from the March’s leaders. They refuse to fully condemn anti-Semitism from virulent anti-Semites such as Louis Farrakhan, leader of the Nation of Islam extremist hate group, they have allegedly made anti-Semitic remarks at planned meetings, and they have delegitimized Israel- the one Jewish state. So should Jews, and others, still participate in the Women’s March? Or should we find more inclusive ways to express our support for progressivism and women’s rights?

Criticism of the Women’s March as it relates to anti-Semitism started to take off in March 2018. In late Feb. 2018, Tamika Mallory, a current leader of the Women’s March, attended a Nation of Islam event at which Farrakhan made detestable anti-Semitic remarks. In Nov 2018, as controversy heated up over this issue, Women’s March founder Teresa Shook called on Mallory and the other co-chairs of the Women’s March to step down in a Facebook post.

“As Founder of the Women’s March, my original vision and intent was to show the capacity of human beings to stand in solidarity and love against the hateful rhetoric that had become a part of the political landscape in the U.S. and around the world,” said Shook in her post.

“In opposition to our Unity Principles, [the Women’s March co-chairs] have allowed anti-Semitism, anti- LGBTQIA sentiment, and hateful, racist rhetoric to become a part of the platform by their refusal to separate themselves from groups that espouse these racist, hateful beliefs,” posted Shook.

Then in Dec 2018, reports surfaced that, according to others involved in planning the march, Mallory and fellow Women’s March co-chair Carmen Perez had personally made anti-Semitic remarks. At a meeting to plan the first Women’s March, Mallory and Perez allegedly “asserted that Jewish people bore a special collective responsibility as exploiters of black and brown people,” and had even “claimed that Jews were proven to have been leaders of the American slave trade.”

In response to the troubling reality that the Women’s March leaders had aligned themselves with anti-Semitism, several local Women’s Marches dropped their affiliation with the national March, such as the Washington State chapter. A number of prominent progressive national organizations have also dropped their affiliation with the national March, such as the Southern Poverty Law Center, Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense, and the Democratic National Committee.

When we rightly call out President Trump for refusing to reject, and for dog-whistling at white supremacists after the deadly 2017 clashes in Charlottesville, Va., but we don’t call out Women’ March leaders’ resistance to condemn anti-Semites such as Farrakhan, we lose moral credibility. Shari Schwartz, a 56-year-old retired federal analyst agrees.

“I can’t march with women who oppose one hate monger but refuse to condemn another,” said Schwartz, who lives in Vienna, Va, in a Washington Post article.

But it is a long way from achieving this reality. Its leaders, through their actions, have alienated Jews who are committed to issues such as women’s rights as well as to their religion and Israel.

Rachel Lachenauer, a 29-year-old D.C. resident who identifies as a progressive queer woman, despises progressive circles that cause her to feel unwelcome because of her support for Israel.

“I won’t participate in a situation that makes me choose between my identities. I’ve been a Jew my entire life, and I’ve been a feminist my entire life. There is no way to separate those things for me,” said Lachenauer in a Washington Post article.

Some people, however, feel that countering the strain between Women’s March leaders and Jews is best done by staying involved in the March and fixing it from the inside.

Laurie Solnik, a 65-year-old federal retiree who lives on Capitol Hill agrees with Nadelman. “We need to seek more common ground,” said Solnik in a Washington Post article. “You don’t do that by turning your back.”

Dr. Jessica Kirzane taught eighth and ninth grade World History at the Hyman Brand Hebrew Academy (HBHA). Currently the Lecturer in Yiddish at the University of Chicago, Kirzane feels that “while the [Women’s March] has particular leadership, it is much more than the official leadership – it is a grassroots community of women and their allies who are only strong if they remain a community, committed to supporting one another.” She also added that “in my opinion, such a community is only possible if we keep talking to one another, and keep working together. The Women’s March represents for me much more than Tamika Mallory’s attendance at the Nation of Islam event.”

However, Kirzane does admit that she “didn’t attend a Women’s March this year – largely because my kids are no longer at an age where it is easy to drag them along with me to these kinds of events. And I will say that all of the hoopla about anti-Semitism in the movement did give me pause, and if personal circumstances had not made it difficult for me to attend (an easy cop out) I’m not sure what my decision would have been.”

Gavriela Geller, Executive Director of Kansas City’s Jewish Community Relations Bureau/American Jewish Committee, says that “there is no one prescribed solution to this issue.”

“The issues you bring up about anti-Semitism in the Women’s March are very real. And, it is also true that they invited three prominent Jewish leaders—Abby Stein, April Baskin, and Yavila McCoy—to join the leadership of the Women’s March in the weeks leading up to the March. Some may say too little too late, but I do think that represents an acknowledgement of the issue and a desire to improve,” Geller says.

She also says that “if we really seek to change the hearts and minds of people we want to be our allies, it does require the ability to engage and to be forgiving as they learn and grow.”

“We may ask ourselves,” adds Geller, “what do we gain as a community by drawing red lines in the sand? What we lose, at least, is a seat at the table, the chance to form real relationships that have the chance to lead to deeper understanding. This is often an uncomfortable and painful process.”

“On the other hand, I want to validate Jewish women who felt so deeply hurt and betrayed by the Women’s March leadership’s ongoing relationship with Farrakhan, inability to fully condemn his words, and perpetuation of anti-Israel bias, that they did not feel comfortable in that space,” Geller says. “Those are real problems and it is not incumbent upon any woman to swallow her pain for the sake of moving forward. In that case, I also support the women who decided not to attend the Women’s March, and hope that instead they will put their passions and energy towards other avenues of making change.”

Adam Tilove is the incoming Head of School at HBHA. His view of this issue is in line with Geller.

“I believe that one must follow one’s inner compass on this one. It is totally legitimate to support the Women’s March for the changes they want to make, and to stand united in solidarity for these changes. Politics make strange bedfellows- meaning you can fight together with people in one arena, and fight against those same people in another,” says Tilove.

Tilove says that he doesn’t think “the fact that some of the leaders are personally anti-Zionist is a disqualifying factor in participating in the March, which has officially distanced itself from anti-Semitism.”

“At the same time,” Tilove says, “if one feels uncomfortable attending the march, if they feel their energies would be better spent in other ways, or if they don’t want to be seen as supporting an organization that is in any way anti-Zionist or anti-Semitic, they should feel comfortable supporting women’s rights in another way.”

While I understand and appreciate the argument for staying involved with the Women’s March, I personally think that we should find more inclusive ways to express our support for progressivism and women’s rights. I do believe that equating or raising anti-Semitism from the left higher than that from white supremacist groups is disproportionate. After all, it is white supremacists who are killing Jews in synagogues and carrying out violence against Jews, such as in Charlottesville. However, speaking as a liberal Jew, I do not think that means we should not call out and denounce anti-Semitism on the left as well as that from white supremacist circles. I know that the Women’s March leadership has taken some steps to address anti-Semitism at the March- but addressing is not the same as unequivocally denouncing. I still believe that much work lies ahead for the Women’s March to fully realize its mission of inclusion for all. And until the Women’s March, as a national organization, takes genuine steps to fully conduct itself in the spirit of true inclusion, I cannot take part in it. Instead, I will continue to fight for progressive change via avenues that welcome all. I believe anti-Semitism is reprehensible, no matter the source, and will always fight it no matter what.

CORRECTION: In a previously published version of this article, the writer wrote the following: Tilove says that “the fact that some of the leaders are personally anti-Zionist is a disqualifying factor in participating in the March, which has officially distanced itself from anti-Semitism.” Unfortunantly, the writer failed to preface those words with: Tilove says that he doesn’t think “the fact that some of the leaders…”. The writer regrets this oversight and any confusion it has caused. – The Editors.