Slider image by Dennis Krolevich

For the past few months, the fundamentals and origins of American music theory scholarship have succumbed to a series of admonishments and whistle-blowing, leading to a constant, unresolved conflict in the media. Not only that, but the very industry of American music education is being accused of being dominated by whites and structural white supremacy. How could one come across such a seemingly atrocious accusation about the sacred, rich art of American and European music, and is it at all plausible?

Let us begin with the prime instigator of this discussion: Dr. Phillip Ewell of Hunter College, N.Y.. Ewell received his Ph.D. in music theory at Yale University and is now associate professor of music theory at Hunter College. He began his endeavors in studying race and gender in Western music while receiving inspiration from scholars such as Ibram Kendi, Joe Feagin, and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva.

His thesis about Western theory is quite simple: “Whiteness and maleness, together, have kind of shoved everything else that is not both white and male to the side – in music theory, in the United States.”

In his argument, Ewell presents a few statistics that physically present how whites dominate Western theory. The Society of Music Theory (SMT) was 84.2 percent white compared to a black population of 0.7 percent out of 1,154 members in 2018.

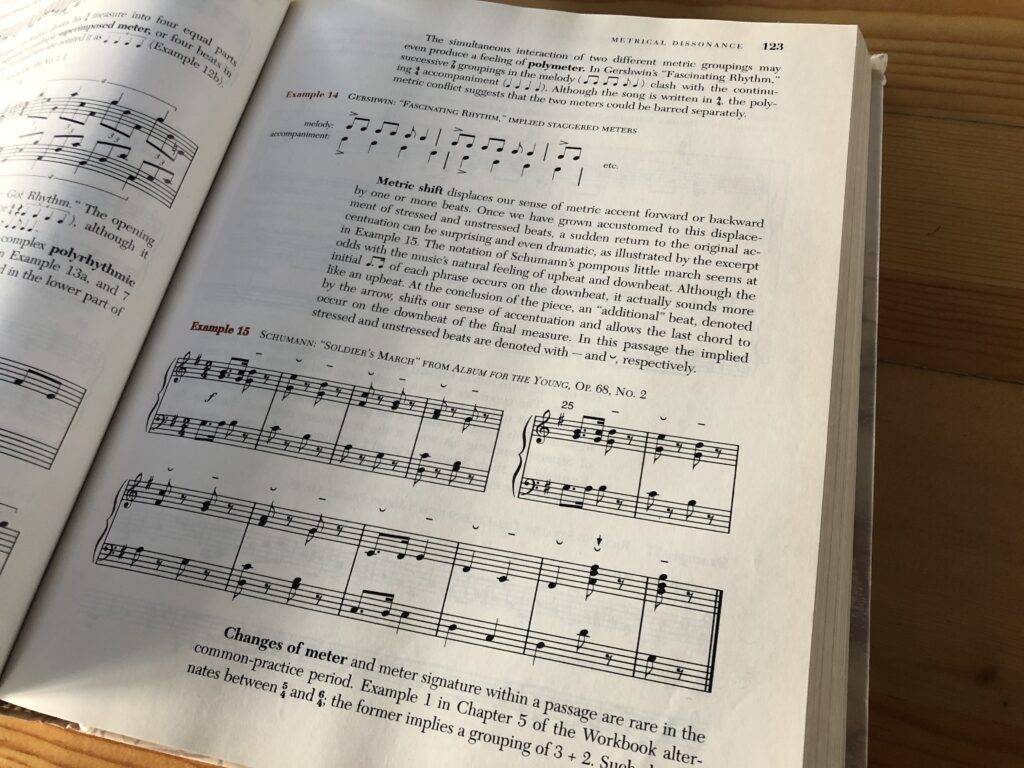

Secondly, he himself conducted a study with a colleague, Megan Lyons, that analyzed seven music theory books that made up 96 percent of the market value for the musical examples provided in the textbooks. In this study, Ewell found that among 2,930 examples of musical literature presented, 49 examples were written by non-whites.

Dr. Michalis Koutsoupides, a local professor of theoretical studies, orchestra, strings, and music technology at Avila University, has something different to contribute to the discussion. He bases the white dominated theory textbooks as being completely a matter of geographical location and historical background.

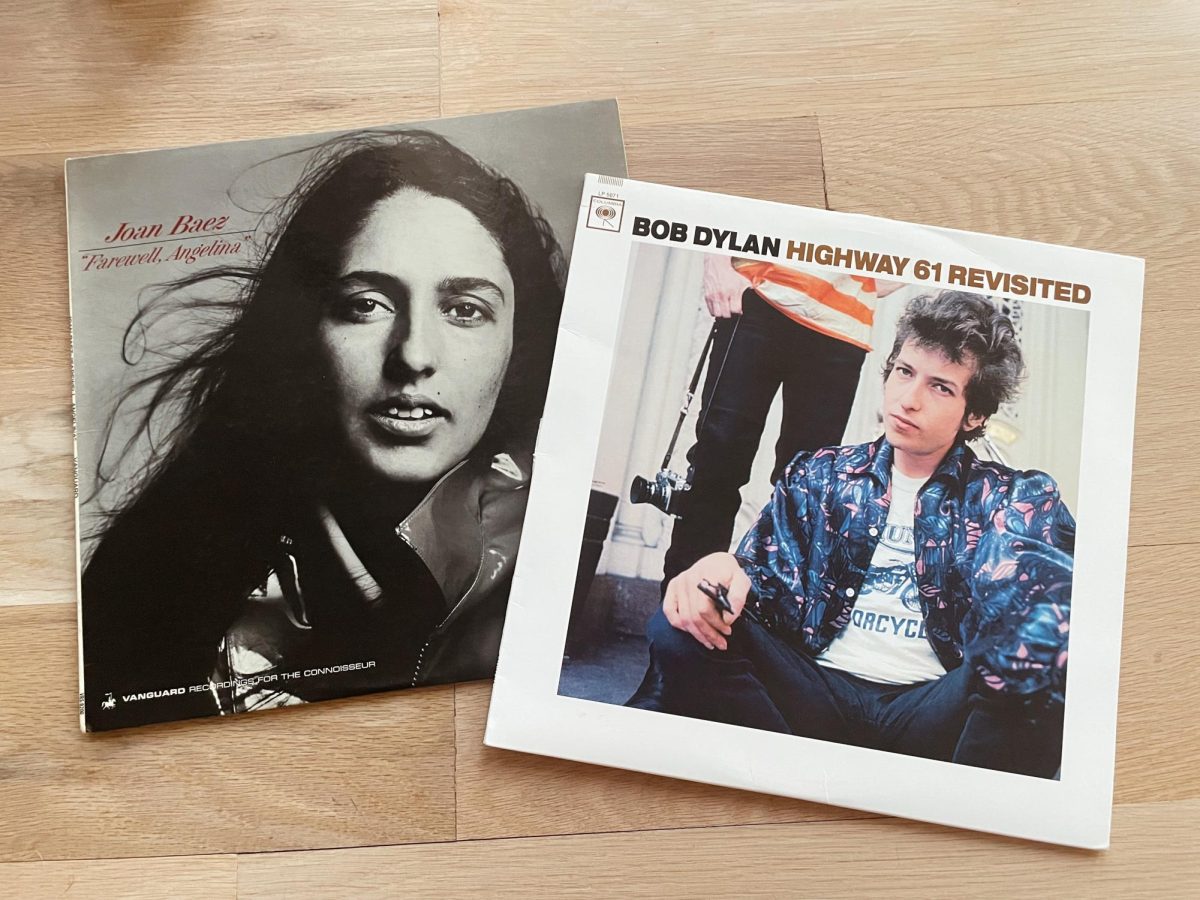

According to Koutsoupides, the composers that wrote “Western sounding” music lived in the very place where this music was being developed. He also mentions that, “If you take any [Western] theory textbook, the first disclaimer is ‘This is a study of Western European music.’” With both of these factors brought together, the conclusion is simply that Western musical culture is dominated by whites because of the geographical context and that it can be studied as a culture separate from American culture. Koutsoupides points out that after the second World War, American music had its own sound. Composers such as John Cage, Berg, and Schoenberg as well as musical theories such as atonality, minimalism, and the 12-tone series system did not reflect the expression of art that was prominent in the Baroque, Classical, or Romantic periods of European music.

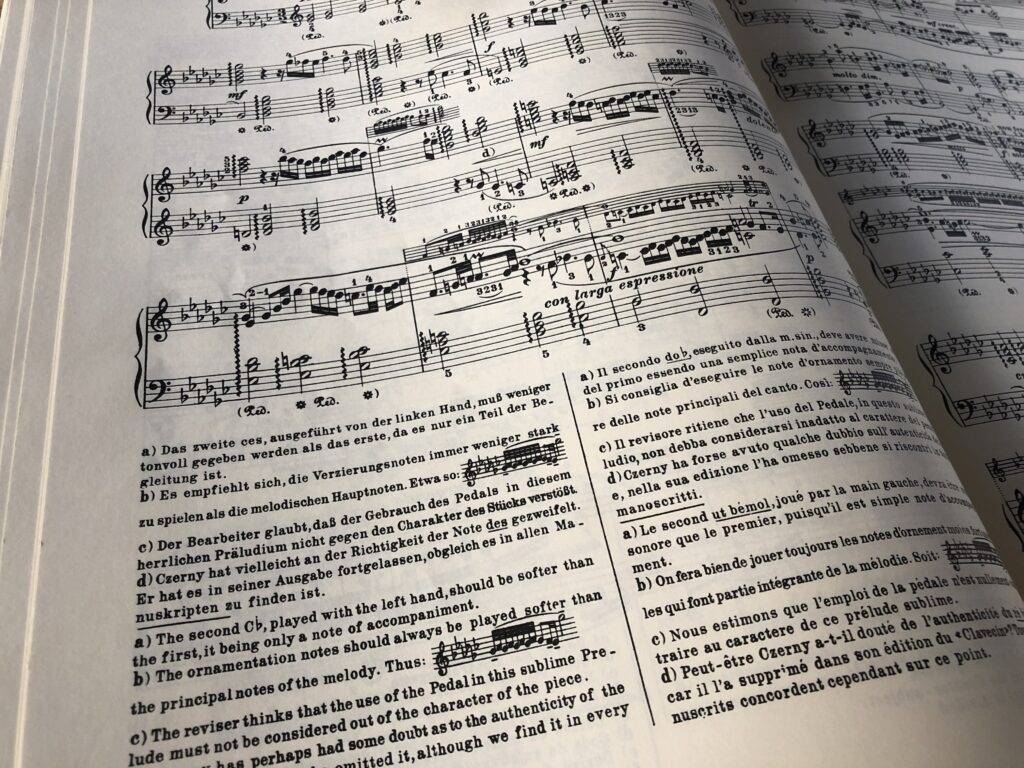

The next figure that Ewell condemns is Austrian music theorist Heinreich Schenker, who established and influenced the American music education that we know and learn today. Most importantly, Schenker invented Schenkerian analysis, and according to Ewell, learning his theories is usually a requirement to receiving any sort of music degree. Simply put, Schenkerian analysis is the method of observing the fundamental progression in any music piece all the way out to the basic overarching progression starting with the tonic, going to the dominant, and returning to the tonic.

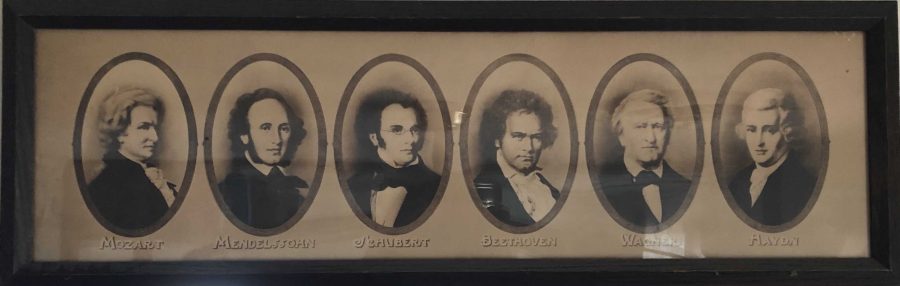

Unfortunately for him, he was a German nationalist and a fervent racist. Ewell recalls in detail Schenker’s diaries and personal writings where he casually expresses his thoughts both on music and ethnic or race superiority. In fact, Schenker himself said that his ideas and biases in music and race were considered as his unified view on the world. What this means is that Schenker’s scholarship idolized the music and culture of whites, specifically Germans, over the music and cultures of the Japanese, Slavs, and blacks. Ewell uses Schenker’s personal ideology and influence upon American music theory to be a prime perpetrator of white and German dominance in Western theory and music. In today’s world, German speaking composers such as Beethoven, Bach, Mahler, and Wagner are so ingrained into classical music theory that German has become a common language requirement to receive a degree in music. Ewell sees this as a direct connection from Schenker’s German nationalism to our music education today.

On the other hand, Koutsoupides has differing thoughts on Schenker’s influence and relevance to our musical education today. He believes that not only is Schenkerian analysis an overgeneralization unnecessary to understanding musical works, but it is also a completely isolated theory in itself.

“To me, it’s not a valuable course to teach,” says Koutsoupides.

According to him, its value has diminished over the years and does not fully represent the education necessary to become a learned musicologist or earn a degree in music. As he mentioned before, American music was not reminiscent of the European traditions before the 20th century nor was it reminiscent of the composers the Schenker himself idolized in his theory.

In regards to language and whiteness, the message Koutsoupides relays is the following: “I don’t think [nationalism] should be reflecting back to looking at Western music and saying Western music is racist because white people lived in Europe at the time when it was being developed and that’s who [had] composed in that language.”

To him, it simply makes sense that certain languages are required in studying Western theory because of the language the composers utilized at the time, and he also believes it is an important and beneficial study for singers, composers, and any musician. Koutsoupides does note that more variety in learning language should be promoted, or in other words, instead of just learning German, students could have a variety of studies in French and Italian as well, since those three are generally the most used in Western musical notation.

Regardless, it was problematic that Schenker saw his analysis not as a theory of music, but a theory of genius. Any music that was not applicable through the lens of Schenkerian analysis was non-genius, illegitimate, or inferior. The catch is that in the 11 examples Schenker provides in using his theory, are all written by classical white composers, only two being non-German speaking composers. It is safe to say that there are some connecting dots to the equation here. Schenkerian analysis is a fundamental component of receiving a degree in music, was created by a racist German nationalist, and only the works that are able to be analyzed by Schenkerian analysis are legitimate.

In his exposure of Schenker, Ewell disclaims that his motive is not to diminish or cancel the teaching of Schenkerian analysis or European composers, but rather to educate students on the history of the theory that they learn today and to encourage the representation of composers with diverse backgrounds, races, and ethnicities. Koutsoupides concurs with the concept of teaching both the academics and the person behind it and treats it in the same way as teaching or performing the works of Richard Wagner, a German composer of the mid-19th century who is known to have anti-Semitic views.

“Yeah, we study Bach. But instead of studying Bach for 30 percent of the core curriculum, let’s study him for 1 percent,” Ewell speculates. “He’s still going to be named – but he’s going to have to share the table with other people who are underexplored.”

Lastly, and most importantly, Ewell seeks only to spark a well deserved discussion amongst musicians and theorists about the racial element in teaching music today. He recognizes that the taught concept of being colorblind is the sole reason why music theory was enabled to be the way it is today, and so in discussing the issue Ewell hopes to inspire thoughts and actions about the injustice in theory so that it is not left ignored.

Ewell, in his determined mission, has one main mantra that he follows in pursuing his scholarship: “There can be no anti-racist action in the future without acknowledgment of and reconciliation for racist actions in the past.”

Though this discussion is one that can be isolating and controversial, perhaps it is beneficial to the everlasting fight for social justice and equality in our nation. Does Western music theory in and of itself elicit white supremacy, or is it not that simple? Eventually, each musical scholar will have to decide that for themselves, and then use the knowledge they have to better educate those around them.